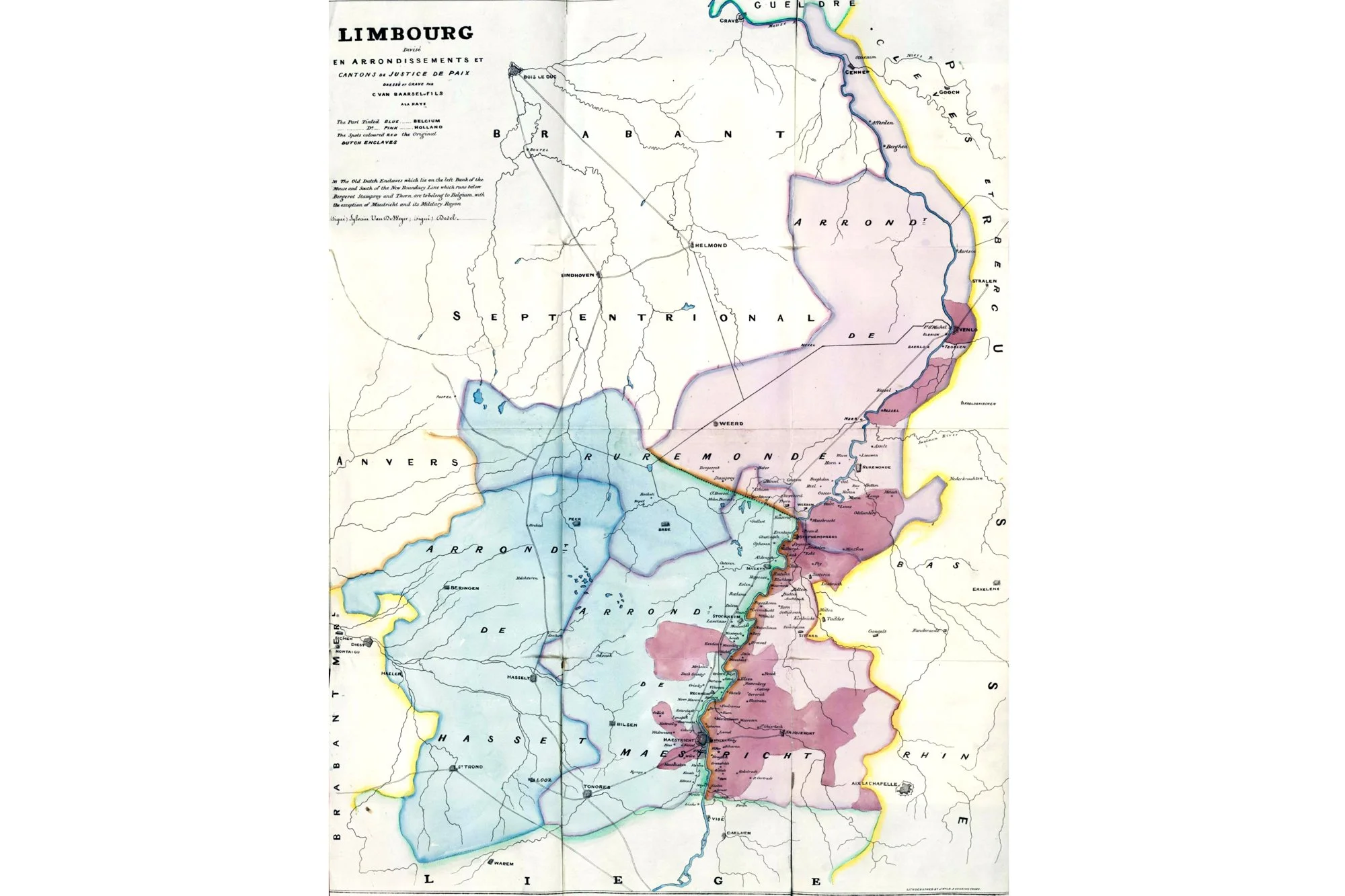

A map with the division of Limburg from the Treaty of XXIV Articles (London, 1839).

When revolution erupted in Brussels in 1830, Limburg found itself at the nexus of Europe’s great powers. For nine uneasy years, the province lived in political limbo. Belgium had declared independence; the Netherlands refused to let go. In the meantime, Limburg’s towns and villages experienced a tug-of-war not just between two capitals, but between two different worlds.

Much of Limburg’s population sided—openly or quietly—with the Belgian cause. Catholic to the core, many Limburgers felt culturally and spiritually closer to Belgium and its Church than to a Protestant-dominated Dutch state. The Catholic Church became both an anchor and a shield: an institution that spoke their language, celebrated their feast days, and upheld traditions that had shaped village life for centuries. In the uncertain 1830s, clinging to the Church was as much an act of identity as it was of faith.

Politically, the situation was volatile. In the early months of the Belgian Revolution, places like Sittard, Roermond, and Venlo joined the uprising; only Maastricht held out for the Dutch king, guarded by its fortress commander. Diplomacy played out in London’s conference rooms, with maps repeatedly redrawn—first in the so-called XVIII Articles of 1831, then in the far harsher XXIV Articles of 1839. These final terms carved Limburg in two, assigning the eastern half, including Maastricht, to the Netherlands.

The decision was met with resentment on the ground. Limburgers had grown accustomed to the broader freedoms they enjoyed under Belgian administration during the 1830–1839 interlude. Many resisted the new Dutch order: over 3,500 people formally opted for Belgian nationality, and thousands more quietly crossed the border. Even for those who stayed, the bond with “Holland” was thin. Daily life—markets, schooling, professional networks—often still pointed south to Liège, Hasselt, and Brussels rather than north to Amsterdam or The Hague.

In this climate, the Catholic Church’s role deepened. It provided continuity in a time when political allegiance was in flux. Parish life, religious festivals, and clergy influence became subtle markers of a Limburg identity distinct from the Dutch national narrative. For decades afterward, this sense of difference lingered. By the time Limburg was fully integrated into the Netherlands in the late 19th century, its Catholic heritage was not just a religious fact—it was a quiet statement of who they were, forged in the shadow of a political split.

Further reading

Piet Lenders, Honderdvijftig jaar scheidingsverdrag België–Nederland en de opsplitsing van Limburg, 1989

W. Jappe Alberts, Geschiedenis van de beide Limburgen, 1972

K. Schaapveld, Local Loyalties: South Limburg During the Belgian-Dutch Separation, 1998

L. Cornips, Territorializing History, Language, and Identity in Limburg, 2012