I’m Sofiia, 18 years old, and I’m from Kharkiv, a city in eastern Ukraine, close to the Russian border. Until February 2022, my life was what you’d expect for a 15-year-old girl. I went to school, played sports, had friends, made plans. My world felt safe and simple — or so it seemed.

That all changed on February 24. My mother woke me up that morning and said: “Sofiia, the war has started. You’re not going to school today. We have to pack.” At first, I didn’t understand. As a kid, I even thought: no school, maybe I can stay in bed a bit longer. But then we spent days sleeping in the bathroom, between two thick walls. I heard bombs. I saw tanks passing by. We lived on a major road from Russia. Anything could happen at any moment.

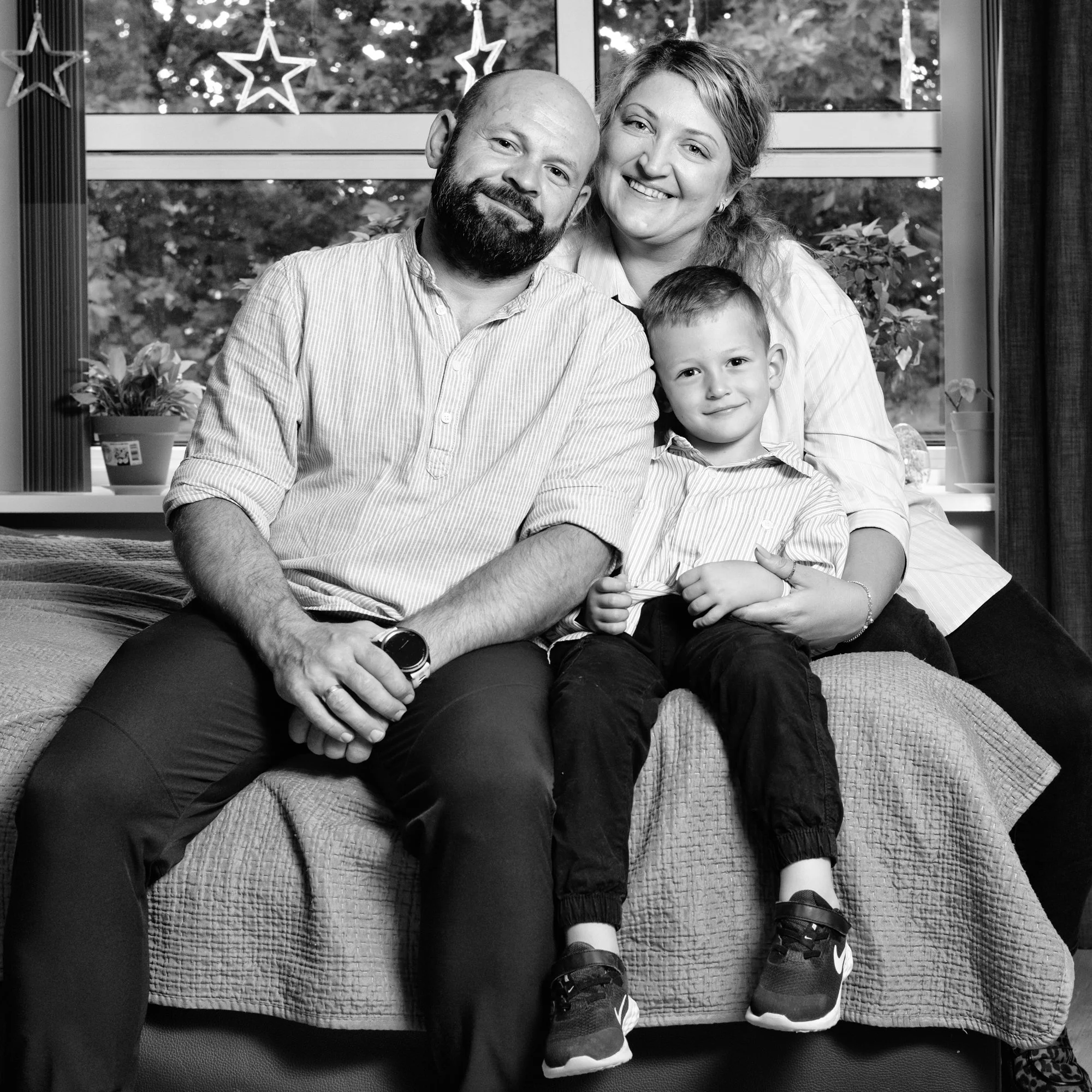

My parents and I fled westward. What should have been a one-hour drive took eighteen hours. We slept in gyms, schools, and in places where strangers opened their doors to those in need. Eventually, we arrived in Chernivtsi, near the Carpathian Mountains. That’s where we made a decision that split my life in two: my mother and I would go to the Netherlands, while my father stayed behind. He couldn’t abandon his company or his employees. It broke our hearts, but there was no other option.

Through a friend of my mother’s, we ended up in Roermond. My mother didn’t speak any English, so I took on all the responsibility — documents, meetings, housing. I was fifteen, but suddenly I was no longer a child. In Ukraine, I had never been especially ambitious. But something shifted. I started school at Nt2 Mundium College in Roermond, a school for newcomers. The teachers saw me, supported me, and believed in me. They gave me confidence. I began learning Dutch, took extra courses, and became interested in marketing and international business. Things started to go well.

I now work part-time in an outlet store and volunteer at the Holland Ukrainian House in Maastricht, and a volunteer social media assistant at Meet Maastricht. I’m also doing an online university degree from Ukraine while preparing for a new chapter: I’ve been accepted to Maastricht University to study International Business. The admission process wasn’t easy — I didn’t meet all the requirements, had to submit extra documents, file an appeal, and prove my motivation. But I made it!

And still… everything I’m building here, I carry with mixed feelings. My father still lives in Kharkiv. His company is still running, our old apartment is still there — as if an angel is watching over it, because several bombs have fallen nearby. He lives under constant stress. When he visits us in Roermond, he even says he misses the adrenaline of danger. “You get used to it,” he says. But I also see what it’s done to him — how his thinking has changed, how heavy it all is for him.

My mother struggles. She’s trying to learn the language, but with no clarity about whether she can stay in the Netherlands, it’s hard for her to make decisions about her life. She doesn’t know whether her future lies here or back in Ukraine. Everything is uncertain. I try to support her — as I’ve done from the beginning. But I see how hard it is for her to live in this world of insecurity, without her home, her friends, her husband, her sense of certainty.

My older sister now lives in Spain with her husband and three children. They happened to be there on holiday when the war started, so they didn’t have to flee in a panic. They’re building a new life in Valencia. My cousins are scattered across Europe. Our family has been torn apart.

I don’t know what the future holds. I’d like to stay in the Netherlands — I feel at home here. I’m learning, growing, and I want to give something back. But for now, I only make small plans. After the war, you learn that everything can change in an instant. You become flexible — maybe too flexible. I always need a plan B.

War doesn’t just change your country. It changes your mind, your heart, your family. And still, I try to look forward. Because I’ve learned to. Because I have no other choice. Because I believe that building — even in small steps — is the only way not to break.