The façade of the Cathedral of Bourges rising above the narrow streets of the old town.

In the quiet center of France stands one of the most remarkable Gothic churches in Europe: Saint-Étienne Cathedral in Bourges.

At first sight it looks like many other medieval cathedrals—towers, flying buttresses, and stained glass rising above the rooftops of the old town. But Bourges reveals its uniqueness the moment you begin to explore it, both inside and outside.

The cathedral tells its story not only through space and light, but also through sculpture.

A Bold Vision of the Gothic Age

Construction of the cathedral began in 1195, under Archbishop Henri de Sully. The eastern end was built first, followed during the thirteenth century by the nave and façade. The church was finally consecrated in 1324.

What makes Bourges exceptional is its plan. Unlike most Gothic cathedrals, it has no transept. Instead of forming a cross shape, the building stretches forward in a continuous space composed of five parallel aisles running the full length of the church.

The central nave rises high above two layers of side aisles, creating a powerful sense of depth and perspective that draws the eye toward the choir.

Geometry in Stone

Medieval builders believed that geometry reflected the divine order of the world. At Bourges this idea becomes visible in the architecture itself.

The cathedral appears to follow a carefully structured system of proportions. The plan and the vertical structure are closely related, giving the building an extraordinary sense of unity. Even today, Bourges feels less like a collection of separate parts than like a single architectural idea carried consistently through the entire structure.

The Sculptures Above the Doors

Before you even enter the cathedral, however, one of its most striking features awaits you above the great portals of the west façade.

These sculpted scenes—known as tympana—form a vast stone narrative carved above the entrance doors. In the Middle Ages they functioned almost like a public book, telling biblical stories to a largely illiterate population.

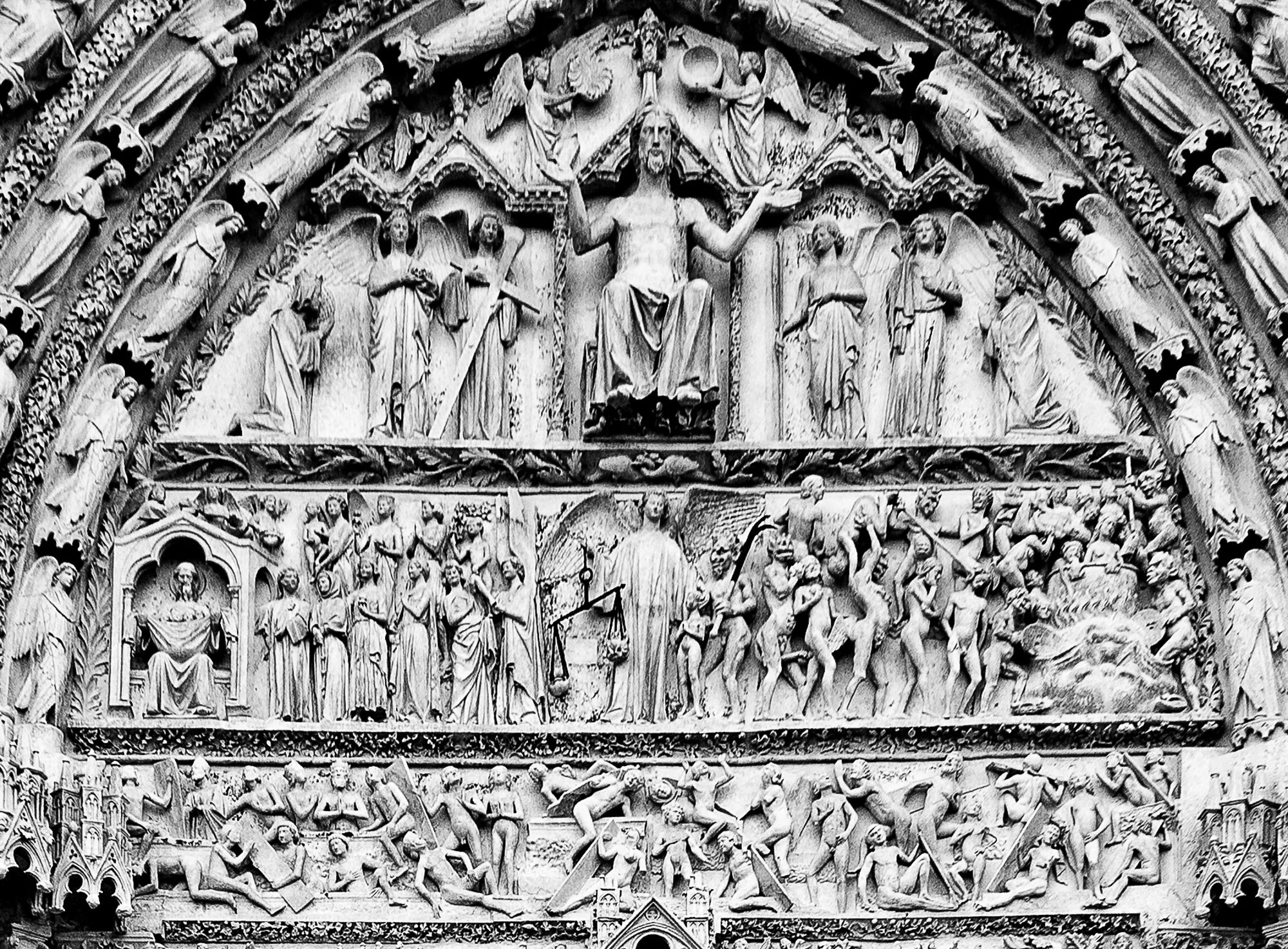

The Last Judgment carved above the central portal of Bourges Cathedral.

The central portal presents a dramatic vision of the Last Judgment. Christ sits in majesty at the center while angels, saints, and resurrected souls fill the scene. Below, the dead rise from their graves while demons drag the damned toward hell. The imagery is both vivid and deeply human: fear, hope, redemption, and justice all appear in the carved figures.

The portals on either side depict other episodes from Christian tradition, creating a sculptural introduction to the sacred space inside.

For medieval visitors arriving in Bourges, the message would have been unmistakable: this building was not just a church, but a gateway between the earthly world and the divine.

Beneath the Cathedral

Below the choir lies another fascinating space: the vast crypt. Because the cathedral was partly built over an old ditch near the Roman city walls, medieval builders constructed a massive substructure to support the new church.

Today the crypt holds sculptures, fragments of earlier decorations, and the tomb of Jean, Duke of Berry, the great patron famous for the illuminated manuscript Les Très Riches Heures.

A Quiet Masterpiece

Bourges Cathedral is now recognized as one of the great achievements of Gothic architecture and has been listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Yet compared with more famous cathedrals such as Chartres or Notre-Dame in Paris, Bourges often feels surprisingly calm.

Perhaps that makes it easier to notice what medieval builders understood so well: that architecture, sculpture, geometry, and light can all work together to tell a story.

At Bourges, that story is still written in stone.