The Death of Meleager — marble relief carved in 11th-century Rome, reusing and reinterpreting ancient Roman motifs of the dying hero surrounded by mourners. Originally part of the Borghese Collection, later set into the façade of the Villa Borghese (1615), and now held in the Louvre Museum, Paris.

The Scene

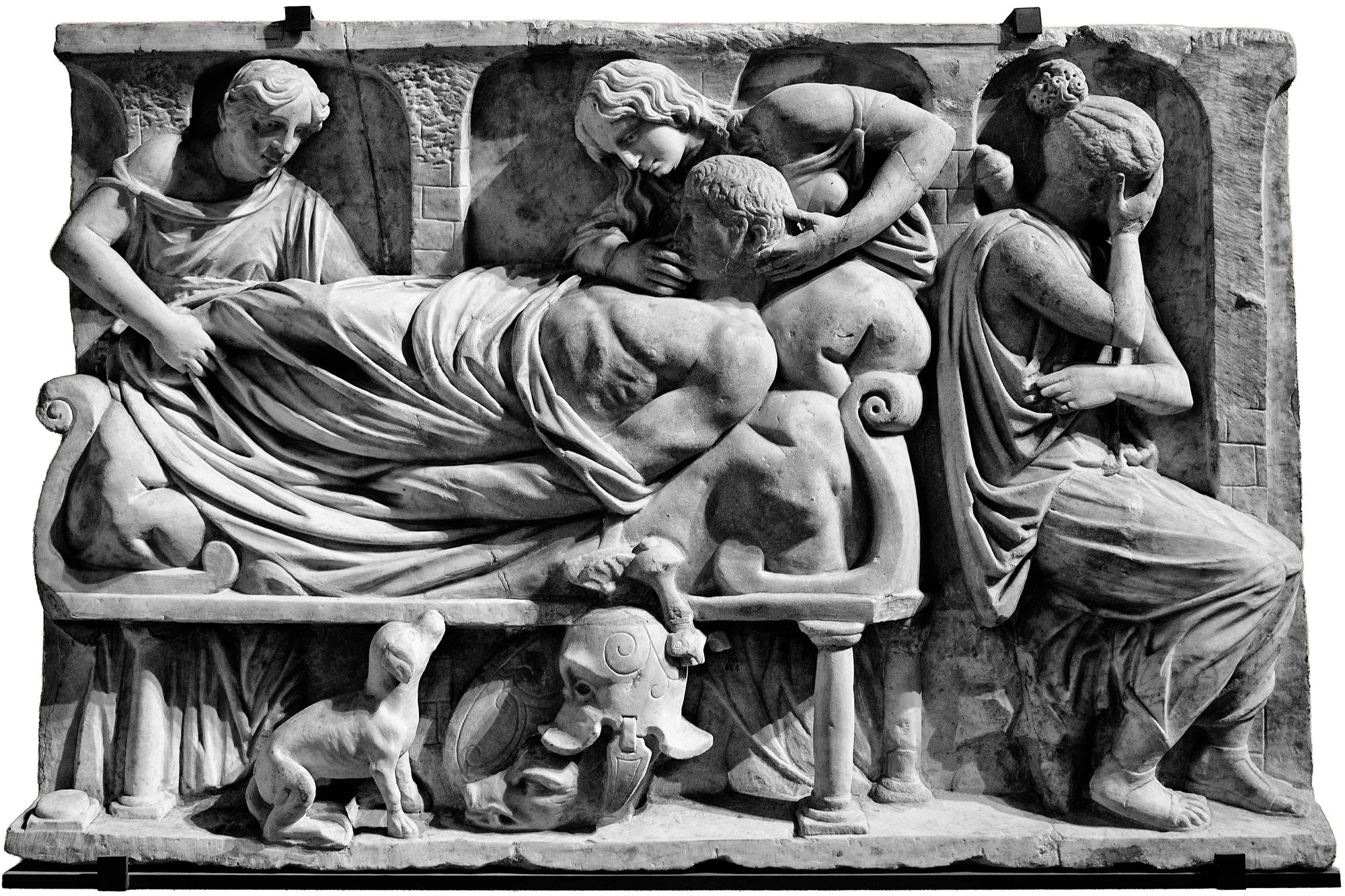

Carved in marble in 11th-century Rome, this relief — known as The Death of Meleager — belongs to the Borghese Collection and now resides in the Louvre Museum, Paris. Though created long after antiquity, it reinterprets a classical myth that had already inspired countless Roman sarcophagi: the dying hero Meleager, surrounded by mourning women.

Meleager reclines on a couch, his body still strong but lifeless. Two women bend over him in grief — one supporting his shoulders, the other touching his face — while a third sits aside, her head veiled and her hand raised to her brow in a timeless gesture of sorrow. At the foot of the couch, a small dog waits faithfully beside a fallen helmet and shield, reminders of the hero’s warrior life. The figures are enclosed within deep niches, suggesting both an architectural setting and a tomb-like space.

The Meaning

In classical myth, Meleager’s death followed the Calydonian boar hunt and his fatal conflict with his own kin. Yet in this medieval version, the story has been transformed: no longer a mythic tragedy, but an image of human mortality. The sculptor, working in a Roman workshop of the 1000s, drew directly from ancient prototypes — perhaps even reusing a fragment of a Roman sarcophagus from the 2nd century CE — but gave it new devotional gravity.

Where ancient art emphasized heroic death, this version speaks in the visual language of compassion and lament. The gestures are quieter, the faces more introspective. The ancient Meleager becomes here a universal symbol of the dying man, surrounded by those who remain.

Reflection

Inserted into the façade of the Villa Borghese (Rome) in 1615 and later transferred to the Louvre, the relief bridges more than a millennium of art and faith. It shows how medieval artists continued to look back to Rome, not to revive its mythology, but to inherit its humanity. In this marble scene — the fallen hero, the grieving women, the silent dog — the boundaries between myth, memory, and prayer have dissolved.

Further Reading

J. Elsner, Art and the Roman Viewer: The Transformation of Art from the Pagan World to Christianity

C. Metzler, Sculpture in Rome, 1000–1150

M. Greenhalgh, The Survival of Roman Antiquities in the Middle Ages