Sainte Thérèse de l’Enfant-Jésus with ex-voto plaques of gratitude, inside the Eglise Saint-Martin, Veules-les-Roses (France).

The Little Flower’s Short, Radiant Life

Thérèse Martin was born in 1873 in the quiet Norman town of Alençon, France, the youngest of nine children in a deeply devout family. Her mother died when Thérèse was four, and the family soon moved to Lisieux, where the Carmelite monastery would shape her destiny.

At just fifteen, Thérèse entered the Carmel of Lisieux, living a cloistered life of prayer and simplicity. Her “Little Way” of holiness—doing small things with great love—became the hallmark of her spirituality. She never left the convent walls and died of tuberculosis at only twenty-four (1897), yet her posthumously published autobiography Story of a Soul swept across the Catholic world.

From Hidden Nun to Canonized Saint

The power of her quiet witness was such that Pope Pius XI beatified her in 1923 and canonized her in 1925, an unusually rapid recognition. In 1997 Pope John Paul II proclaimed her Doctor of the Church, a rare honor for a woman, underlining the universal depth of her simple yet profound theology of trust and love.

Normandy’s Living Heart of Devotion

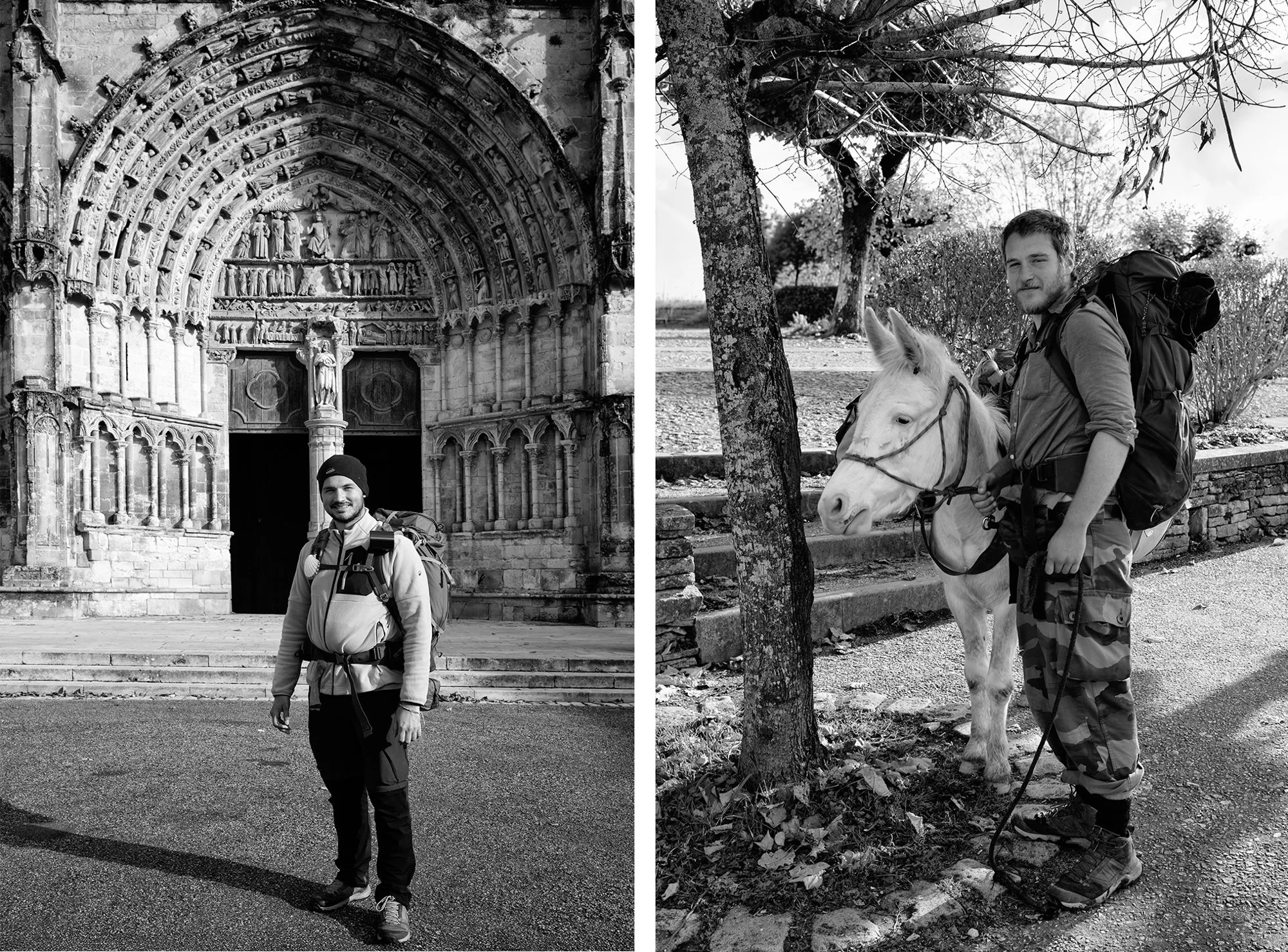

Though Thérèse is venerated worldwide, Normandy remains the heart of her devotion. Lisieux is home to the grand Basilica of Saint-Thérèse, a major pilgrimage destination drawing over a million visitors annually. Pilgrims come to walk the streets she knew, to pray in the Carmel where she lived and to touch the atmosphere of the family home “Les Buissonnets.”

The region’s attachment runs deep: Thérèse embodied the quiet perseverance and earthy faith long characteristic of rural Normandy. Her promise to “spend heaven doing good on earth” resonates in a landscape where faith is expressed less in spectacle than in steady, heartfelt fidelity.

Even along the Somme coast, in places like Veules-les-Roses, small churches keep her image close—testimony to how her “Little Way” crossed every parish boundary.

Why She Still Matters

Saint Thérèse invites modern seekers to discover the sacred in daily tasks and fleeting acts of kindness. In an age of noise and ambition, her life whispers that holiness is found not in grand gestures but in quiet love.

Further reading

Thérèse of Lisieux, Story of a Soul

Ralph Wright, Little Thérèse: Doctor of the Church

Guy Gaucher, The Story of a Life