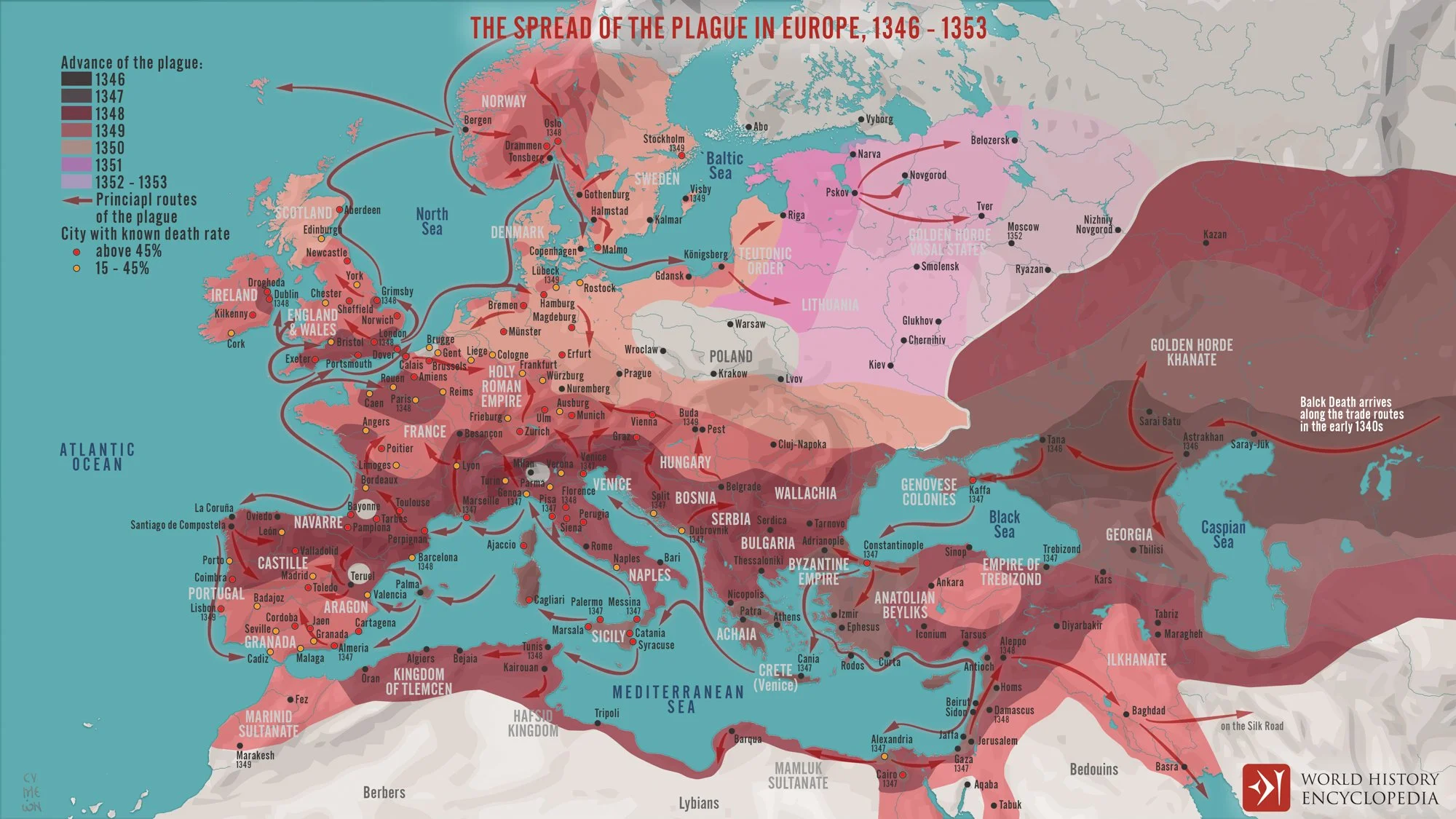

The Spread of the Plague in Europe, 1346–1353" by Simeon Netchev. © World History Encyclopedia. Licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Available at: https://worldhistory.org/image/12038/the-spread-of-the-plague-in-europe-1346---1353.

Plagues were not new to Europe. Outbreaks had come and gone for centuries, often leaving sorrow in their wake. But in the late 1340s, something changed. A new wave of plague struck Europe with a force no one had seen before—or since.

It began in 1347, when trading ships arrived in the Sicilian port of Messina. Onboard were dead or dying sailors—and rats carrying fleas infected with Yersinia pestis. Within months, the disease spread across the Mediterranean and deep into the heart of Europe. This time, it didn’t just take lives—it shattered an entire world.

A Pandemic Unleashed

Between 1347 and 1353, the plague tore across the continent in wave after wave. Within six short years, it claimed the lives of an estimated 25 to 50 million people—between 30% and 60% of Europe’s population.

Though plague outbreaks would return regularly in later centuries, this first explosion was by far the most deadly. No region was untouched, but some places suffered extraordinarily high mortality rates:

Cities hit especially hard:

Florence: ~60% mortality (~60,000 deaths out of ~100,000 inhabitants)

Paris: ~50% mortality (~100,000 deaths out of ~200,000 inhabitants)

London: ~45% mortality (~40,000 deaths out of ~90,000 inhabitants)

Venice: ~60% mortality (~60,000 deaths out of ~100,000 inhabitants)

Avignon: ~55% mortality (~11,000 deaths out of ~20,000 inhabitants, recorded in just a few weeks)

Barcelona: ~40% mortality (~16,000 deaths out of ~40,000 inhabitants)

By 1351, the plague reached Poland and parts of Russia. In many towns, entire neighborhoods were abandoned. Fields went untilled, shops closed, and churches fell silent. The dead were buried in mass graves, sometimes without rites or names.

Death and Transformation

The Black Death brought chaos—but also change. With fewer workers, wages rose. The old feudal order began to erode. Many questioned the authority of the Church, especially as priests and bishops died alongside commoners.

Fear led to violence. In parts of Europe, Jewish communities were scapegoated, accused of poisoning wells, and brutally massacred. Elsewhere, people turned to religion, mysticism, or radical movements like the flagellants.

Yet from the ruins, something new slowly emerged: a deeper awareness of human fragility—and a spark of cultural transformation that would later blossom into the Renaissance.

A Timeless Warning

Art from the time, like the famous Danse Macabre, shows death leading kings, cardinals, and beggars hand in hand. The message was clear: no one escapes the dance.

The Dance of Death: The Cardinal and the King

This woodcut depicts two powerful figures—a cardinal and a king—being led away by personifications of Death. It is part of the Danse Macabre tradition, a late medieval allegory that reminds viewers of the inevitability of death, regardless of rank or status. The image originates from the 1490 edition of La Danse Macabre printed by Guyot Marchant in Paris, one of the earliest and most influential printed versions of this theme.

Centuries later, this moment still haunts us—not just for its suffering, but for how it changed the world.