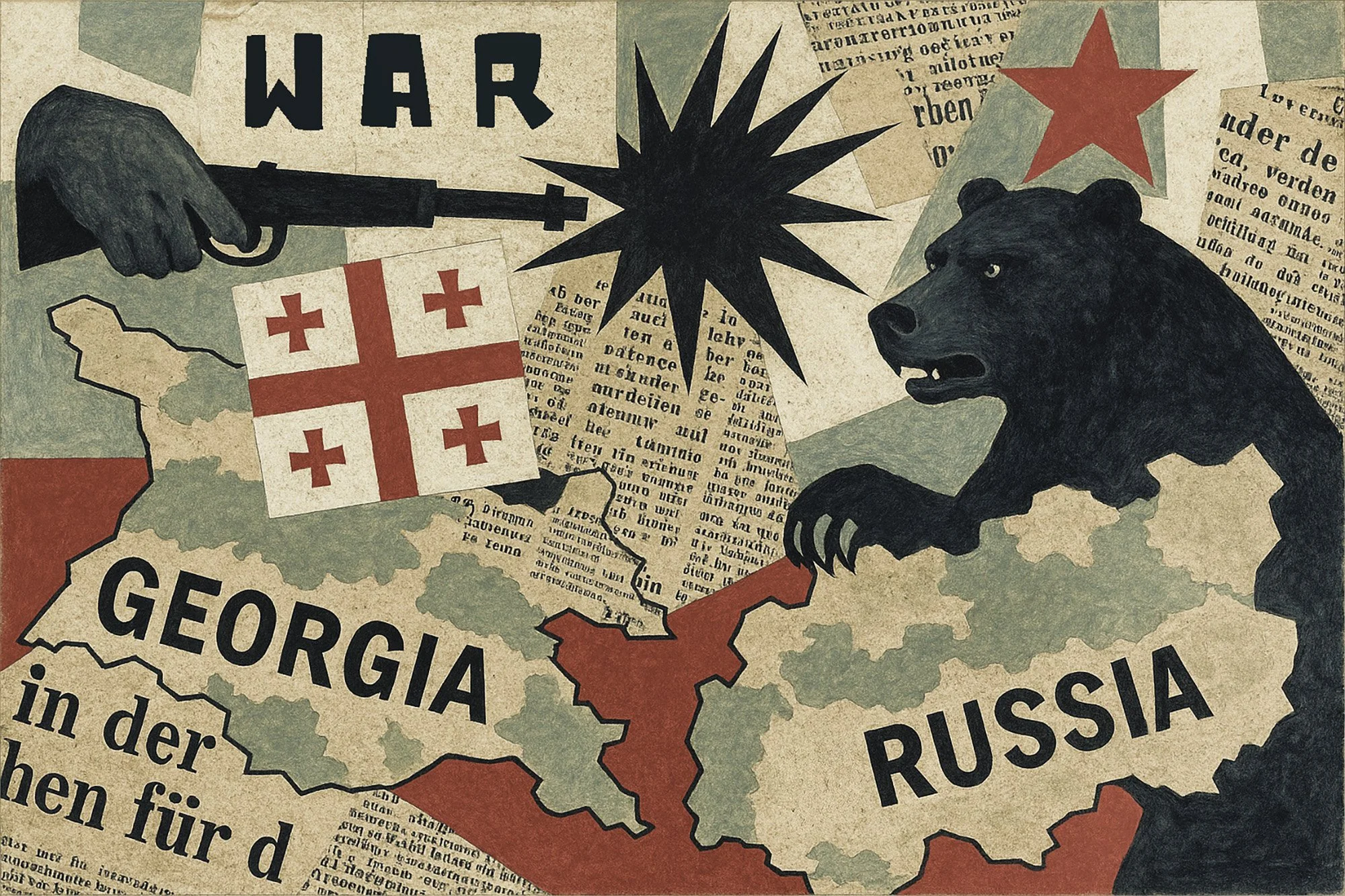

The events of February 24, 2022, marked the most dramatic rupture between Russia and the West since the Cold War. In the early hours of the morning, Russian forces launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine from multiple directions — pushing south from Belarus toward Kyiv, east from Russia into the Donbas, and north from Crimea into the southern regions of Kherson and Zaporizhzhia. The Kremlin framed it as a “special military operation,” but its scale and ambition made clear it was a war to redraw borders and reshape Europe’s security architecture.

The Failed Blitzkrieg

Moscow’s plan for a lightning strike — seizing Kyiv within days, decapitating Ukraine’s leadership, and installing a pro-Russian government — collapsed in the face of fierce and determined resistance. Ukrainian forces, bolstered by volunteers and armed with Western-supplied anti-tank and anti-aircraft weapons, halted the advance. The battles for Kyiv, Kharkiv, and Mykolaiv became early symbols of defiance. By April, Russian troops withdrew from the north, leaving behind evidence of atrocities in towns like Bucha, and concentrated their efforts on the eastern front.

A War of Attrition

With the initial gamble failed, the conflict shifted into a grinding war of attrition. Artillery duels, long-range missile strikes, and the increasing use of drones became defining features of the battlefield. The siege and destruction of Mariupol shocked the world, as tens of thousands of civilians endured bombardment, shortages of food and water, and forced evacuations. Millions of Ukrainians fled abroad, creating the largest refugee crisis in Europe since the Second World War. Meanwhile, Western sanctions hit Russia hard, freezing assets, severing banking connections, and limiting access to critical technologies — though high global energy prices kept Moscow’s war machine funded.

The Expanding Battlefield

By 2023 and 2024, the war’s intensity did not diminish. Both sides adapted technologically: Ukraine integrated Western air defenses and precision-guided munitions, while Russia ramped up drone and missile production with the help of Iran and North Korea. The Black Sea became another contested arena, with Ukraine striking Russian naval assets and supply lines to Crimea. Fighting spread to previously quieter sectors, and both armies dug deeper into fortified positions reminiscent of the First World War.

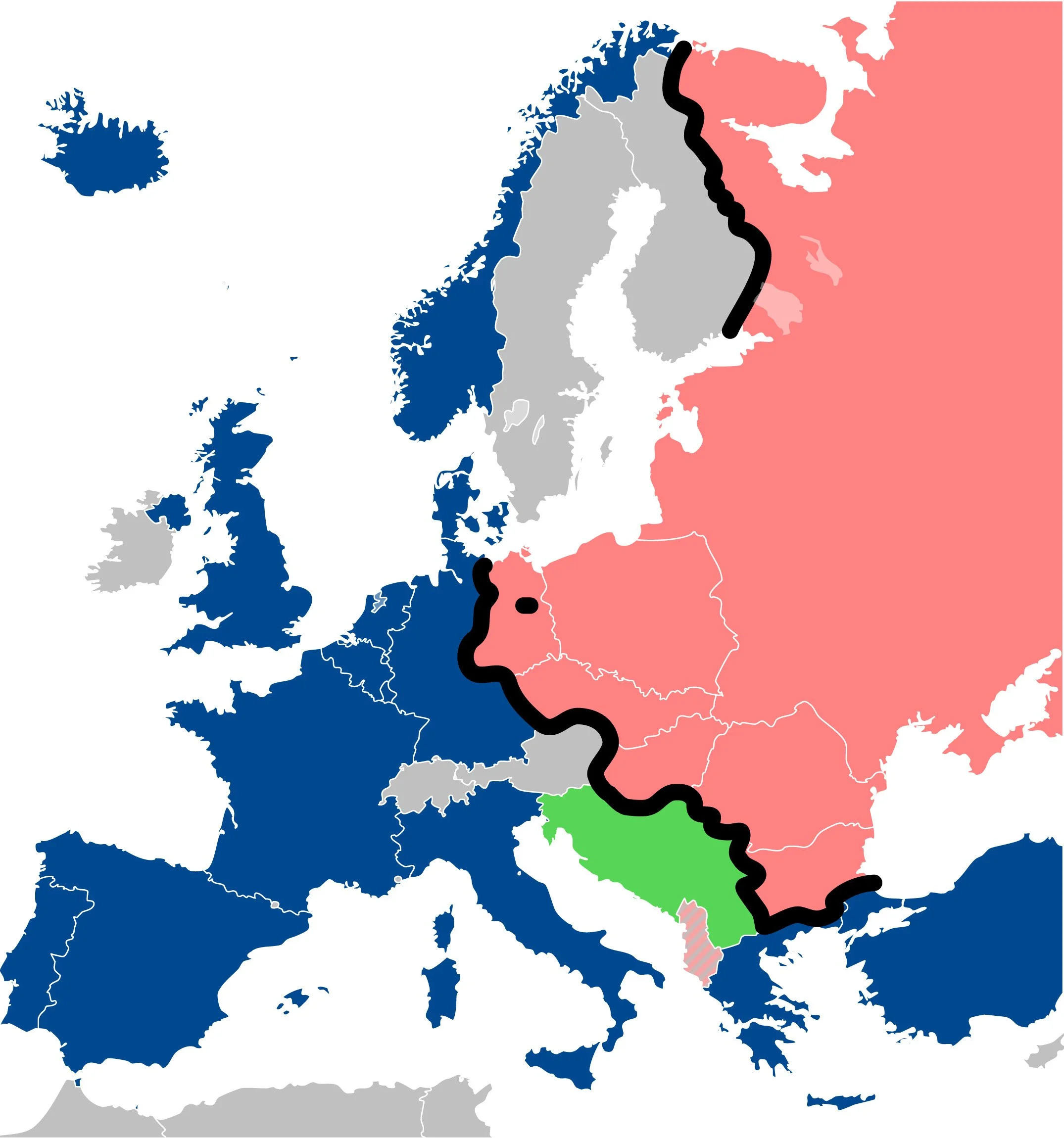

Global Realignment

Russia’s isolation from the West drove it into a tighter embrace with China, India, Iran, and North Korea, forming a loose but significant network of states willing to trade, share technology, and counterbalance Western influence. NATO, far from fractured, expanded to include Finland, with Sweden on the way — a strategic setback for Moscow. The European Union accelerated its energy diversification, ending decades of dependence on Russian gas. The war shattered the assumptions that had underpinned Europe’s post–Cold War order, reviving large-scale military spending and long-term security planning.

Shifting Political Currents

Across Europe and beyond, the war reshaped politics. Governments faced pressure over rising energy prices and defense budgets. Populist movements sought to exploit divisions over aid to Ukraine, while others rallied around the need to defend democratic states from authoritarian aggression. In Russia, dissent was met with harsh repression, new laws criminalized criticism of the war, and thousands of political opponents, journalists, and activists fled abroad.

An Uncertain Future

By 2025, the frontlines had shifted only marginally. Neither side could deliver a decisive blow. Ukraine remained steadfast in its goal of restoring its 1991 borders, while Russia showed no sign of relinquishing occupied territories. The costs — measured in lives lost, economies strained, and trust shattered — promised to shape the region for decades to come. Whether the conflict ends in a negotiated settlement, a frozen front, or continued escalation remains one of the central geopolitical questions of the 21st century.

Further Reading:

Luke Harding – Invasion (2022)

Serhii Plokhy – The Gates of Europe (2015)

Mark Galeotti – Putin’s Wars (2022)

Lawrence Freedman – Command (2022)