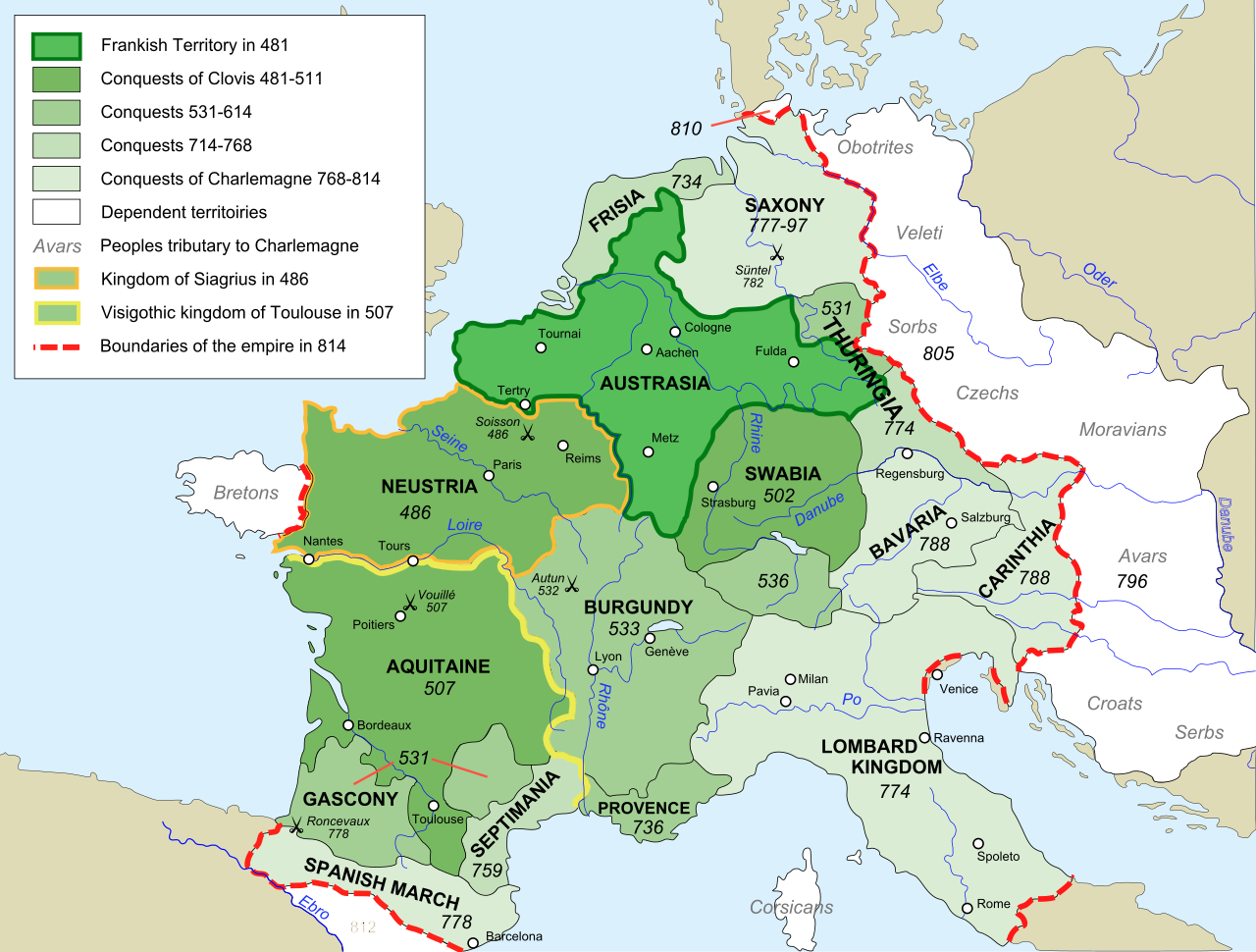

The Expansion of the Frankish Realm: From Clovis to Charlemagne (481–814). (Image: Frankish Empire 481 to 814" by Amitchell125, based on work by Altaileopard, licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.)

On a cold Christmas morning in the year 800, the great Frankish king Charles—better known as Charlemagne—knelt in prayer before the altar of Saint Peter’s in Rome. Behind him, Pope Leo III rose and placed a golden crown on his head, declaring him Imperator Romanorum—Emperor of the Romans. The coronation shocked even Charlemagne. He had spent decades conquering, legislating, and Christianizing, but now he stood at the head of a reborn Western Empire, heir not just to the Franks, but to Rome itself.

From that moment, Europe—particularly what we now call France—was drawn into a centuries-long drama: the struggle between the ideals of imperial unity and the forces of local power. And by the year 1035, that empire had fractured. France, as we recognize it today, was still embryonic: a map not of one kingdom, but of dozens. The King of France, a descendant of Charlemagne in name but not in power, controlled little more than the region around Paris. Dukes, counts, and bishops ruled the rest, each with his own ambitions, army, and sense of sovereignty.

This is the story of how that transformation unfolded—how an empire of dreams gave way to a kingdom of fiefdoms.

The Empire of Charlemagne

When Charlemagne was crowned emperor in 800, his rule already stretched across most of Western Europe. From the Pyrenees to the Elbe, from the North Sea to central Italy, his authority was unrivaled. But Charlemagne was not simply a conqueror. He was a reformer, a legislator, and a deeply Christian ruler who envisioned a unified res publica Christiana—a public order bound by faith, law, and learning.

He promoted Latin education, standardized weights and measures, oversaw land redistribution, and maintained a network of royal agents (missi dominici) to administer justice in his name. His court at Aachen became a center of cultural and administrative revival.

But Charlemagne’s empire was, at heart, personal. Loyalty flowed through oaths to the man, not institutions. And personal empires, as history has shown time and again, rarely survive long beyond their founder.

Fracture and Inheritance

Charlemagne died in 814. His only surviving legitimate son, Louis the Pious, inherited the imperial crown. Louis was a deeply religious man, but lacked his father’s commanding presence. He spent much of his reign trying to balance power between his sons. His attempts to divide the empire while maintaining unity failed, and after his death in 840, civil war erupted.

The empire was finally split by the Treaty of Verdun in 843. Charlemagne’s grandsons—Lothair, Louis the German, and Charles the Bald—divided the realm into three kingdoms. Charles received the western third: West Francia, the core of what would become modern France. But the empire’s dismemberment had long-lasting consequences.

Charles the Bald, and his successors, bore the title of king, but increasingly lacked control over the land beyond their own demesne. Powerful nobles—many of whom had risen in response to invasions and internal chaos—began to dominate local life. Fortified castles sprang up across the countryside. Power, once centralized in the imperial court, now shifted toward the lords of the land.

The Treaty of Verdun (843): Division of the Carolingian Empire Among Charlemagne’s Grandsons. (Image: "Vertrag von Verdun en" by Ziegelbrenner, licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.)

The Viking Factor

Among the most immediate pressures came from the north. In the mid-9th century, Viking raiders—Danes, Norwegians, and Swedes—descended upon the coasts and rivers of West Francia in longships. They plundered monasteries, burned towns, and overwintered in fortified camps. The kings of West Francia were often powerless to stop them.

Rather than wage endless war, King Charles the Simple struck a deal. In 911, he granted land around the lower Seine River to the Viking chieftain Rollo, on the condition that Rollo convert to Christianity and defend the region against future raids. This land became the Duchy of Normandy. Its rulers—originally Norsemen—would become some of the most formidable lords in all of France.

By 1035, the duchy was thriving. Its duke, Robert I (called the Magnificent), had gone on pilgrimage to Jerusalem, leaving his illegitimate son William—still a child—in charge. That boy would become William the Conqueror, and his future conquest of England in 1066 would tie France and England together in centuries of dynastic entanglement.

The Rise of the Feudal Lords

As Normandy emerged, so too did other regional powers. In the southwest, the Dukes of Aquitaine governed vast lands, stretching from Poitiers to the Pyrenees. Aquitaine was culturally distinct, with its own dialect and customs, and its rulers acted with near-total independence.

In the northeast, the Counts of Flanders dominated the economic life of the region, trading with England and the Low Countries. In the center of the kingdom, the Counts of Blois controlled key cities like Chartres, Tours, and Troyes—forming a buffer between the royal domain and the Champagne plains.

And in the rugged land of Anjou, Fulk III, known as Fulk Nerra or Fulk the Black, carved out a reputation as one of the most brutal and effective warlords in France. A brilliant tactician and relentless castle builder, Fulk waged war on his neighbors and expanded Angevin influence across western France. In 1035, he was still alive, nearing the end of his long reign, and preparing to hand power to his son, Geoffrey Martel. This family line—the Angevins—would later give birth to the Plantagenet dynasty, which would rule England and much of France in the 12th and 13th centuries.

A Weak but Persistent Monarchy

All the while, the Capetian kings clung to power. In 987, following the death of the last Carolingian king, the crown had passed to Hugh Capet, Duke of the Franks. Though his election was the beginning of the longest continuous royal line in European history, it was a fragile inheritance. Hugh, and his son Robert II, held sway over only a modest royal domain. Their influence did not extend far beyond the Île-de-France.

By 1035, Henry I had just taken the throne after the death of his father, Robert II. Young and untested, he faced a kingdom dominated by barons who owed him homage in theory, but in practice governed independently. France had a king, but little centralized state.

1035: A Fractured Realm

So what did France look like in 1035?

It was a land of lords, not a unified state. The king ruled in name, but dukes, counts, and bishops wielded true authority. Some were descendants of Carolingian officials; others were former Viking raiders. Local customs, languages, and loyalties often mattered more than the distant king in Paris.

But though fragmented, this was also a time of innovation. Feudal bonds created webs of mutual obligation. The Church expanded its influence, promoting peace and education. Castle-building transformed warfare and society. And the seeds of future conflict—between kings and vassals, between France and England—were being planted.

France around 1035: A Feudal Mosaic of Royal, Ducal, and Ecclesiastical Territories. (Map from The Historical Atlas by William R. Shepherd, 1911 - University of Texas at Austin.)

From Charlemagne to Capet

The year 800 marks the high point of imperial ambition in the West—a moment when one man stood above a continent, cloaked in Roman and Christian authority. The year 1035, by contrast, captures the culmination of disintegration: a time when power was local, fractured, and fiercely contested.

Yet the story does not end there. The Capetians would endure, slowly expanding their power over centuries. The dukes and counts of 1035 would one day become subjects of the crown. And the idea of France—obscured in the patchwork of the early eleventh century—would eventually emerge again, this time more enduring than before.

Further Reading

The Carolingians: A Family Who Forged Europe – Pierre Riché

Charlemagne – Roger Collins

Feudal Society – Marc Bloch

The Capetians: Kings of France 987–1328 – Jim Bradbury

The Normans – Levi Roach

The Plantagenet Ancestry – W.H. Turton

The Origins of the French Nation – Edward James