Image created with AI.

When we travel across Europe, it is almost impossible not to notice the presence of religion. Cathedrals shape skylines. Small shrines mark old roads. Processions still move through villages where people know each other. Whether in a Portuguese hamlet, a Spanish mountain town, or a Flemish square, religion has long shaped landscapes and identities.

But what if we look at religion not only as belief, but also as a way in which human communities learned to live together?

This is the central idea of Darwin’s Cathedral by evolutionary biologist David Sloan Wilson. The book invites us to see religion through the same lens we use to understand cooperation and social life. Not to dismiss it or defend it, but to ask why it has appeared in so many cultures and why it has lasted so long.

Religion and Cooperation

Humans survive by cooperating. We are not the strongest animals, but we are exceptionally good at forming groups. From early hunting bands to modern societies, working together has been our greatest strength.

Yet cooperation is fragile. Every community must deal with selfish behaviour. How do you build trust? How do you encourage people to contribute when no one is watching?

Wilson suggests that many religious traditions grew in part because they helped communities answer these questions. They created shared moral expectations, common stories, and a sense of belonging. They encouraged generosity and discouraged behaviour that harmed the group. People felt accountable not only to each other, but also to something greater than themselves.

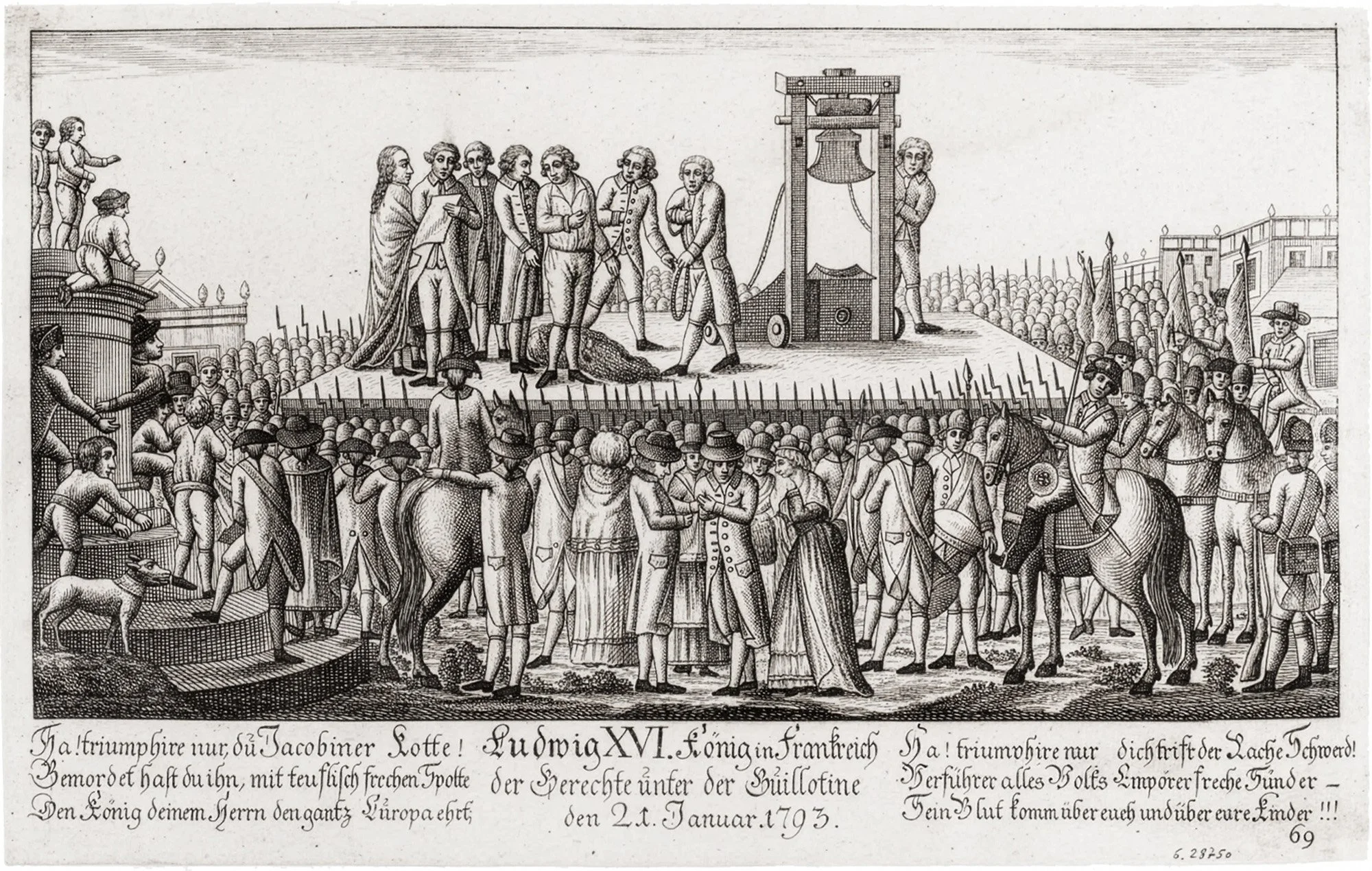

Over generations, communities that were able to strengthen trust and solidarity were often more stable. Those that failed to do so tended to fragment or disappear. In this way, religious traditions were shaped by the practical challenges of everyday life.

The Power of Ritual

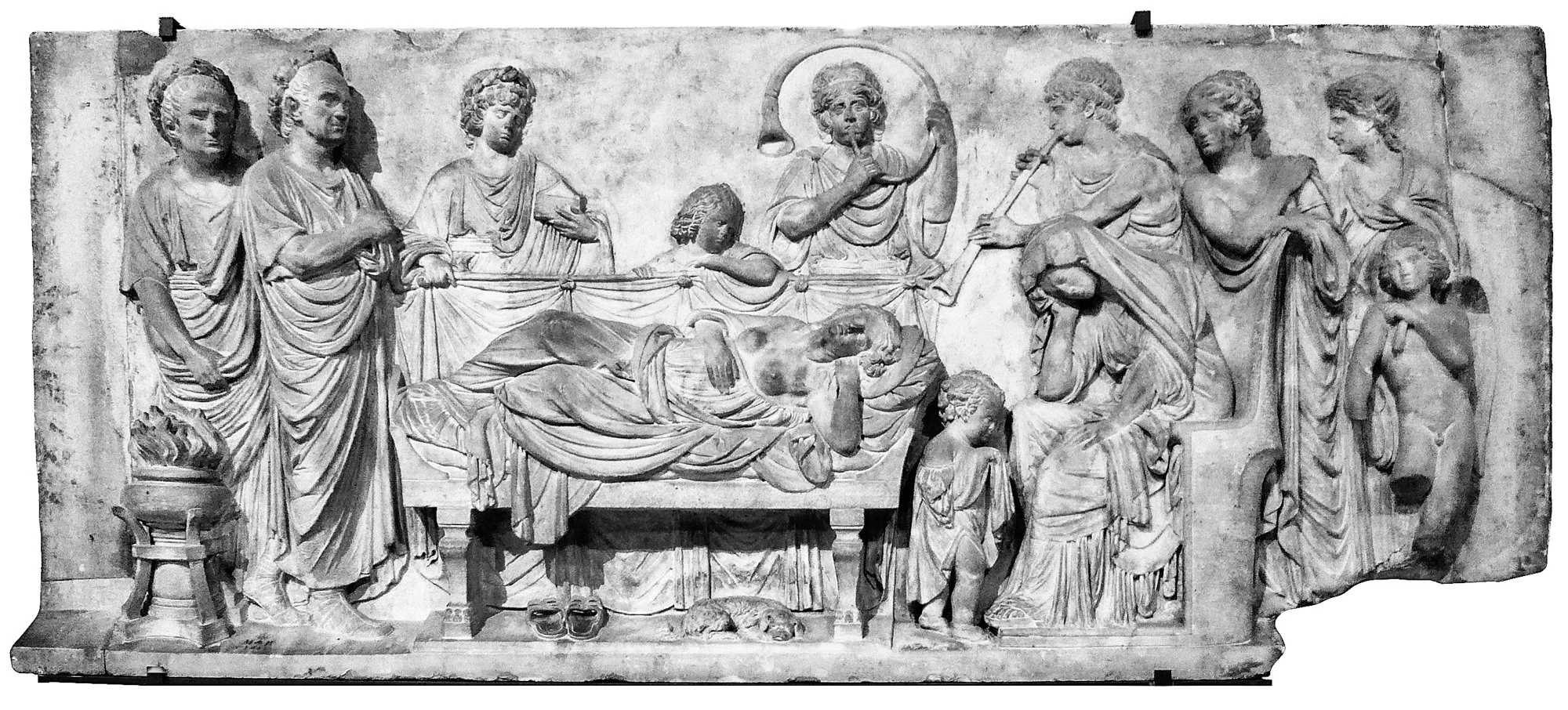

The book also highlights the importance of ritual. From chanting to pilgrimages, rituals may appear mysterious, but they create strong emotional bonds. Anyone who has witnessed a local feast or procession in southern Europe recognises their effect. They bring people together, reinforce memory, and strengthen identity.

Even today, societies that see themselves as secular use similar practices—national ceremonies, commemorations, and shared public events. These moments remind people that they belong to a larger story.

Belief and Behaviour

One of the most striking ideas in the book is that behaviour often matters more than doctrine. In practice, what counts is whether people act in ways that support cooperation and stability.

This helps explain why many religious traditions emphasise visible commitment. Charity, prayer, fasting, and other demanding practices signal loyalty. They show that someone is willing to invest time and effort in the community, which makes trust easier.

Religious communities have also often built strong networks of support. Many hospitals, schools, and welfare systems have roots in these traditions.

A Cultural Traveller’s Perspective

For travellers, this perspective opens a new way of seeing. A cathedral is not only an architectural masterpiece; it is the result of centuries of shared effort. A pilgrimage route is also a network that connected communities, trade, and culture.

Standing in Vézelay, Santiago de Compostela, or a small Romanesque church in rural France, you are looking at the long history of how people learned to organise their lives together. These places show how trust, identity, and cooperation were built across generations.

This approach encourages curiosity rather than judgement. Religion becomes part of an evolving cultural landscape that continues to shape Europe today.

Further Reading

David Sloan Wilson — Darwin’s Cathedral

Joseph Henrich — The WEIRDest People in the World

Pascal Boyer — Religion Explained

Scott Atran — In Gods We Trust