Pilgrims of the Bay (Mont-Saint-Michel, France)

Without Knowing, on the Camino

Each morning he walks the same stretch of the Meuse — unaware that he follows the ancient route of pilgrims bound for Santiago de Compostela.

Every morning, as the mist still clings to the Meuse, people set out from Roermond for their daily walk. Some follow the dike for exercise, others to clear their minds — yet without knowing, their footsteps trace one of Europe’s oldest pilgrim routes.

The Camino de Santiago passes quietly here, unmarked by fanfare or faith, just a worn rhythm between river and sky. The man in the photo has walked this path for years, greeting the same geese, watching the same current. He may never carry a scallop shell or reach Santiago, but his devotion to the road is its own kind of pilgrimage.

Burgos' Dancing Giants: The Gigantillos

The Gigantillos of Burgos.

Close to Plaza de España you’ll meet them mid-step: a bronze couple frozen in a festival beat. The man—wide-brimmed hat, long brown cape, staff of office—leans forward as if to lead. The woman—headscarf, earrings, skirt swirling—answers with a half-bow that might become a spin. This is Los Gigantillos, the city’s beloved “little giants,” cast in bronze by Teodoro Antonio Ruiz and set beside the Church of San Lesmes in 2010.

They don’t just decorate a sidewalk; they guard a story. The Gigantillos are the human-scale cousins of Spain’s towering festival giants. In Burgos they come alive to the sharp call of the dulzaina and the heartbeat of the drum, dancing through Corpus Christi, Curpillos, San Lesmes, and the feast of Saints Peter and Paul. Where they pass, children copy their steps, grandparents clap in time, and the street remembers its own choreography.

The tradition is older than the pavement beneath your feet. Versions of these figures paraded here as early as the sixteenth century; in 1899 the modern pair took shape. A disastrous fire in 1973 forced the city to start again—proof that folklore isn’t fragile when a community chooses to carry it. The bronze couple arrived in our century to mark the centenary of the local savings bank, anchoring the living dance in metal so you can meet them even out of season.

Look closely and you’ll see the city inscribed in details: the mayoral staff in his hand, a civic symbol disguised as stage prop; the cape catching imaginary wind; the tilt of her shoulders that suggests music you can’t quite hear. Take a photo if you like, but better—stand a minute. Imagine the dulzaina cutting the morning air, the drum finding your ribs, and the Gigantillos stepping forward, as they always have, to lead Burgos into its next celebration.

Mores and Christians Festival in Bocairent (Spain)

Early in February, Bocairent bursts at the seams in honour of its patron saint, San Blas (Sant Blai). For six vivid days, fireworks crackle, pasodobles and comparsa music swell, parades roll, processions wind, and gunpowder booms through the streets. Everyone with a tie to Bocairent comes home—students, emigrants, cousins, the old guilds and new cofradías—crowding balconies, drumming in doorways, marching beside standards stitched by their mothers. At the castle, captains parley and boast before the mock assault, the old rivalry reborn in pageantry. By night, lanterns and drums fold the town into a pulsing heart; by day, Sant Blai crosses streets. Half theatre, half memory—history retold on foot to the rhythm of trumpets and gunfire—leaving your ears ringing.

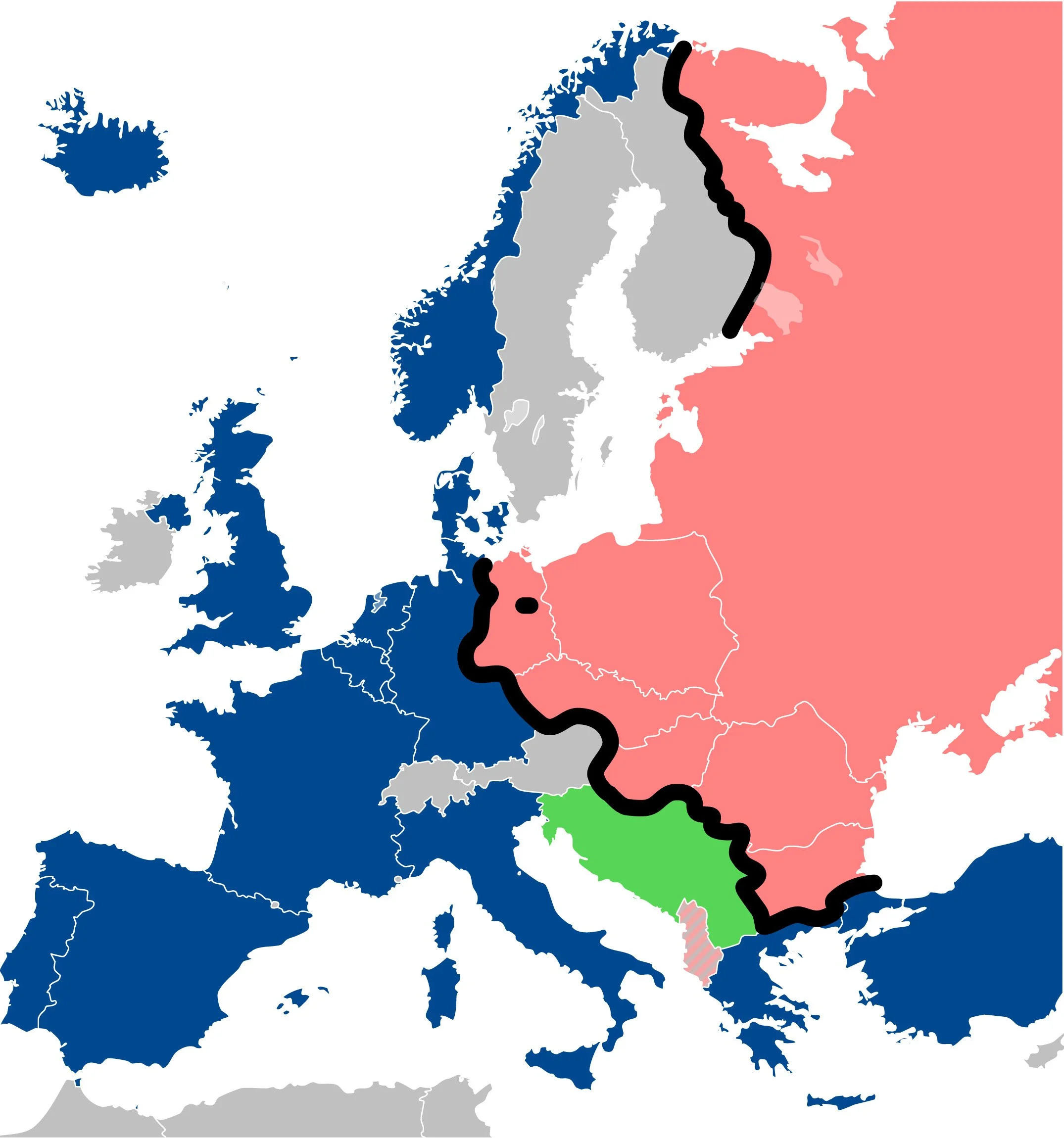

Russia, The Eternal Return of Suppression: The Cold War - Confrontation and Control

Map of post–World War II Europe illustrating the Iron Curtain dividing Eastern and Western blocs. License: © Sémhur / Wikimedia Commons. Licensed under CC BY‑SA 4.0 (Creative Commons Attribution‑ShareAlike 4.0 International).

The end of the Second World War left Europe divided — and the Soviet Union standing as one of two superpowers. The Red Army’s march west had not only defeated Nazi Germany but also planted the seeds of Soviet influence deep into Eastern Europe. What followed was a forty-year geopolitical standoff that shaped the modern world.

The Iron Curtain Descends

By 1947, Winston Churchill’s “Iron Curtain” speech captured the new reality: Eastern Europe, from the Baltic to the Balkans, was under communist governments loyal to Moscow. The USSR created a buffer zone of satellite states — Poland, East Germany, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Romania, and Bulgaria — all bound together through political repression, secret police, and a common economic system, COMECON.

Containment and Confrontation

The United States responded with the policy of containment, pledging to halt the spread of communism. NATO was formed in 1949; the Warsaw Pact, its Eastern counterpart, followed in 1955. The Korean War (1950–1953) saw Soviet pilots secretly fighting for North Korea, while crises in Berlin repeatedly brought the superpowers to the brink.

Cracks in the Bloc

Even within the communist camp, unrest boiled. In 1956, a workers’ revolt in Hungary was crushed by Soviet tanks, killing thousands. In 1968, the Prague Spring in Czechoslovakia — a movement for “socialism with a human face” — was similarly put down by a Warsaw Pact invasion. The Brezhnev Doctrine justified such interventions as necessary to preserve the socialist system.

The Arms and Space Races

The Cold War was fought not only with ideology and armies but also with technology. The Soviets shocked the world in 1957 with the launch of Sputnik, the first artificial satellite, and in 1961 by sending Yuri Gagarin into space. But prestige in space masked economic stagnation at home. The nuclear arms race consumed vast resources, and the fear of mutually assured destruction hung over the globe.

Dissent Behind the Curtain

While dissidents like Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn exposed the horrors of the Gulag, and Andrei Sakharov spoke out for human rights, the KGB ensured dissent was contained. Yet underground movements, samizdat literature, and the whispers of reform kept the spirit of resistance alive.

Further Reading:

Anne Applebaum – Iron Curtain (2012)

John Lewis Gaddis – The Cold War (2005)

Vladislav Zubok – A Failed Empire (2007)

Tony Judt – Postwar (2005)

The great Iberian Ibex

The mounted head of an Iberian Ibex at the ‘Centro de Visitantes Torre del Vinagre’ (Parque Natural de las Sierras de Cazorla, Segura y Las Villas, Spain).

Upon the cliffs, the ibex stands,

With hooves that dance on rugged lands.

Its horns, a crown, both strong and high,

Pierce the edge of earth and sky.Through windswept peaks, in morning light,

It leaps with grace, a fearless flight.

Majestic, wild, and bold it roams,

The mountain’s king, the heights its home.Riquewihr (France)

Riquewihr, France.

Riquewihr is a beautifully preserved medieval town located in the Alsace region of northeastern France, nestled between the Vosges Mountains and the famous vineyards of Alsace. Often referred to as one of the "most beautiful villages in France," Riquewihr is renowned for its half-timbered houses, cobblestone streets, and vibrant flower displays, all set within its 13th-century fortified walls.

Dating back to the Roman era, Riquewihr became prominent during the Middle Ages, flourishing as a winemaking town. Its well-preserved architecture reflects centuries of history, with structures from the Renaissance era and the Middle Ages standing side by side. The town's rich viticultural tradition remains strong, producing some of the finest Alsace wines, particularly Riesling.

Riquewihr’s charm, history, and location along the Alsace Wine Route make it a popular destination for visitors seeking both cultural and gastronomic experiences in one of France's most picturesque settings.

Saint Lucia of Syracuse

The statue of Saint Lucia of Syracuse, Catedral Vieja de Salamanca (Spain)

Saint Lucia, born in Syracuse, Sicily, during the 3rd century, led a life devoted to Christianity. Legend has it that she promised her life to God, vowing chastity and service. Despite persecution by Diocletian, she remained steadfast, even surviving attempts to martyr her. One tale recounts her clandestine visits to Christians in prison, bringing them food and light. She wore a wreath of candles to illuminate her path, symbolizing hope in dark times.

The plate with two eyes, a curious detail, is often attributed to her own actions. In one of the stories, Lucia plucked out her eyes to deter a persistent suitor who admired them. Miraculously, her sight was restored by divine intervention, leaving her with a plate depicting her eyes as a reminder of her unwavering faith and miraculous healing.

Today, Saint Lucia is celebrated on December 13th, embodying the virtues of courage, compassion, and the triumph of light over darkness.

The Church on Friesland’s Highest Mound (Hegebeintum, The Netherlands)

The church at Hegebeintum (The Netherlands).

In the tiny Frisian village of Hegebeintum, the church seems to float above the surrounding fields. It stands atop the highest terp—an artificial dwelling mound—in the Netherlands, rising about eight and a half metres above sea level. Built in the 12th century, the Romanesque church of brick and tuffstone replaced an earlier wooden structure, serving both as a place of worship and as a refuge during floods.

Over the centuries, the church was altered in Gothic style and fortified with a stout tower. Inside, you can still see medieval fresco traces and a richly carved 17th-century pulpit. The terp itself has its own story: much of it was dug away in the late 19th century for fertile soil, leaving the church standing even more prominently against the horizon.

Today, the church and terp together form a striking landmark—a meeting point of human resilience, medieval faith, and the ever-changing Frisian landscape.

The interior of the church at Hegebeintum (The Netherlands).

Dinkelsbühl (Germany)

The Nördlinger Tor, Dinkelsbühl (Germany).

Hidden on Bavaria’s Romantic Road, Dinkelsbühl looks almost too perfect to be real. Encircled by intact 15th-century walls and punctuated by sixteen towers, it feels as if time stopped when merchants and guilds still ruled the cobblestones. But its charm is more than just picture-book beauty.

One of the town’s most intriguing chapters dates back to the Reformation and the Peace of Westphalia (1648). Dinkelsbühl was declared a paritätische Stadt—a “city of parity.” That meant Catholics and Protestants shared power equally, an extraordinary arrangement in a century marked by bitter religious wars. Councils, schools, and even church use were organized to respect both confessions. This rare compromise spared Dinkelsbühl the sectarian violence that scarred so many other towns and shaped a culture of cooperation that lingers to this day.

Stroll the narrow lanes to St. George’s Minster, admire the gabled merchants’ houses, or follow the nightly Rothenburg-style night watchman tour, and you walk through layers of civic peacekeeping as well as medieval splendor.

Dinkelsbühl isn’t just beautifully preserved—it’s a reminder that lasting harmony can grow where tolerance takes root, a lesson as valuable now as it was nearly four centuries ago.

Segringer Strasse, Dinkelsbühl (Germany).

Coal, Catholicism, and Community: Henri Poels and the Social Fabric of South Limburg (1900–1930, The Netherlands)

Henri Poels.

When coal was discovered in South Limburg at the turn of the 20th century, it promised jobs, prosperity—and potential trouble. Across Europe, industrial regions had already shown how rapidly growing workforces could become hotbeds of labour unrest, socialism, and political radicalism. In The Hague and in church offices alike, there was quiet concern: how could Limburg’s mining communities grow without becoming a social powder keg?

That challenge found its champion in Monsignor Henri Poels, a priest from Venray who would become known as aalmoezenier van de arbeid—chaplain to the working class. Poels understood that keeping the peace in the mines meant more than sermons on Sunday. It required housing, leisure, and a sense of belonging firmly rooted in Catholic life. His mission was both pastoral and strategic: to “bind the worker to the soil,” as one famous slogan put it, by giving them a stake in stable, faith-based communities.

In 1911, Poels founded Ons Limburg, a cooperative housing association designed to tackle the chronic shortage of decent homes for miners and their families. Good housing, he believed, was a bulwark against the appeal of socialist promises. But bricks and mortar were only the beginning. Poels actively encouraged a dense network of Catholic associations—sports clubs, choirs, youth groups, and mutual aid societies—that would anchor miners’ lives in a shared moral and cultural framework.

His reach extended into the cultural sphere as well. Through initiatives like the NV Tijdig, he supported Catholic-friendly cinema and theatre, offering wholesome entertainment that kept people within the Church’s orbit even in their leisure hours. In the process, he helped shape a “pillar” of Catholic life in Limburg—parallel to, and often in competition with, socialist and liberal networks.

The results were tangible. Catholic miners’ unions provided an alternative to secular labour movements, offering advocacy on wages and conditions without breaking ranks with the Church. Housing cooperatives ensured that miners lived in neighbourhoods designed with parish life in mind—complete with churches, schools, and clubhouses. For decades, this model of faith-led community building kept Limburg’s mining region socially cohesive, even as it absorbed waves of migrant labour from other parts of the Netherlands, Belgium, Germany, and beyond.

By the 1930s, the coalfields of South Limburg were more than an economic engine; they were a laboratory for a uniquely Catholic approach to industrial society. Poels’ legacy still lingers in the brick façades of garden villages, in the archives of miners’ associations, and in the memory of a time when the Church was not only a place of worship, but the architect of an entire way of life.

Banner of the Dutch Roman Catholic Miners’ Union, Geleen branch in South Limburg (1920).

Further reading

BWSA, Henri Poels (Internationaal Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis)

Canon van Nederland, Limburg-venster: Ons Limburg and housing policy

T. Oort, Film en het moderne leven in Limburg (chapter on associations and cinema)

S. Langeweg, Mijnbouw en arbeidsmarkt in Nederlands-Limburg, 1900–1965

Katholiek Zuid-Limburg en het fascisme (Maaslandse Monografieën 19)

Open Universiteit, “Mijn en Kerk” thematic article

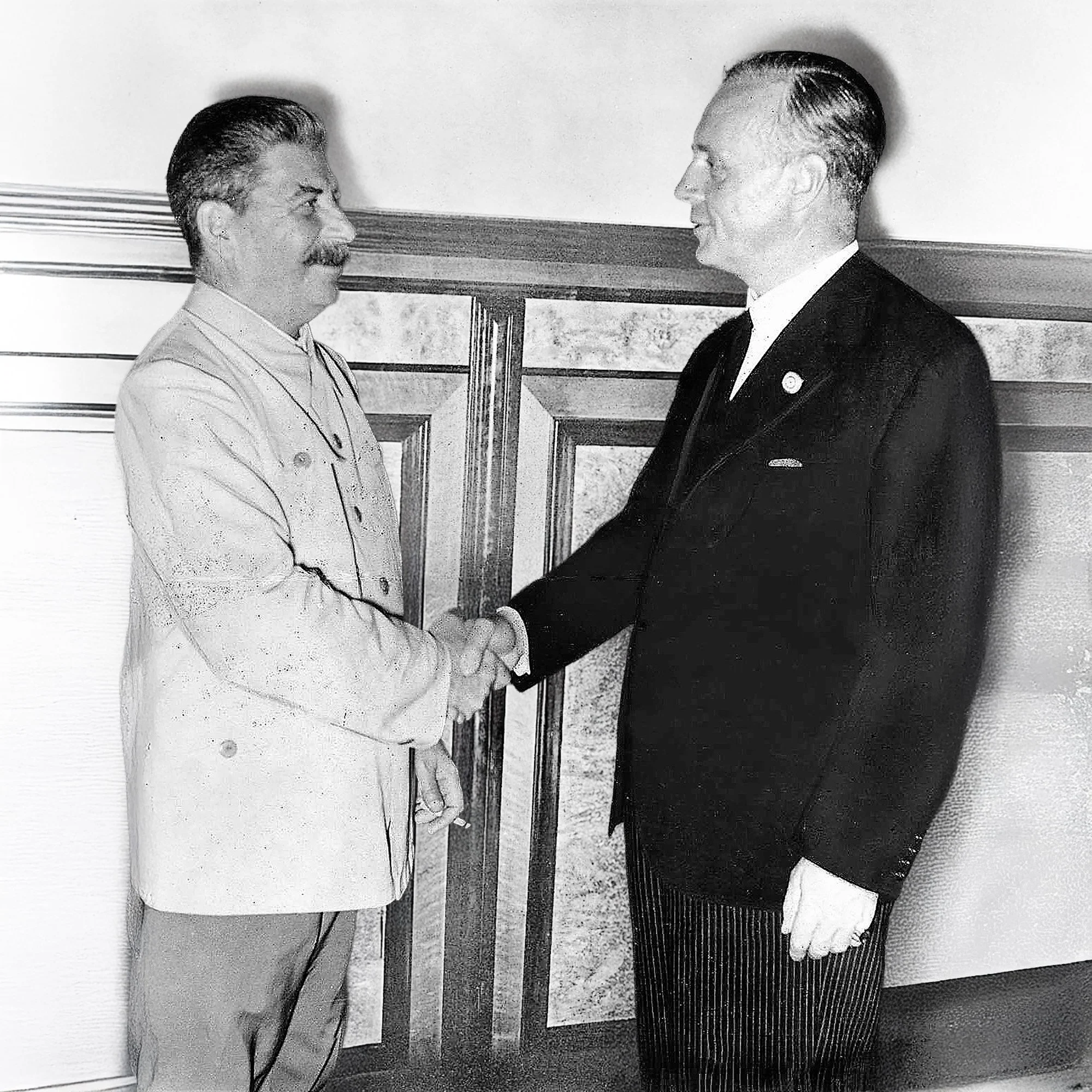

Russia, The Eternal Return of Suppression: The Second World War and a New World Order

Pact with the Devil, Joseph Stalin shakes hands with German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop at the Kremlin, Moscow, 1939. Based on photo: Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-H27337 / CC-BY-SA 3.0 DE.

The Second World War was both a catastrophe and a crucible for the Soviet Union. It transformed the USSR from an embattled revolutionary state into one of the two global superpowers — but at a staggering human cost.

The Pact with the Devil

In August 1939, the world was stunned by the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact. The Soviet Union, sworn enemy of fascism, signed a non-aggression treaty with Nazi Germany. A secret protocol divided Eastern Europe into spheres of influence. When Germany invaded Poland from the west on September 1, the Red Army marched in from the east two weeks later, seizing territory promised in the pact. Within a year, the USSR had annexed the Baltic states and parts of Romania, and waged a bitter war against Finland in the Winter War of 1939–1940.

Operation Barbarossa: The Shock

At dawn on June 22, 1941, Germany launched Operation Barbarossa, the largest military invasion in history. Three million German soldiers, supported by allies, surged into Soviet territory. Stalin had ignored multiple warnings from Western intelligence and his own spies, convinced Hitler would not break the pact so soon. The result was chaos: Soviet forces were encircled, millions captured, and vast swathes of land overrun in the first months.

A War of Survival

Yet the Soviet Union did not collapse. Moscow did not fall. The Soviet leadership relocated industry east of the Urals, away from German bombers. Ordinary citizens endured unimaginable hardship — cities under siege, villages burned, families torn apart. The Siege of Leningrad lasted 872 days, killing over a million through starvation, shelling, and cold. The Battle of Stalingrad (1942–1943) became the turning point: a brutal, house-to-house struggle that ended with the surrender of an entire German army.

The Road to Berlin

From Stalingrad onward, the Red Army went on the offensive. In 1944, Operation Bagration annihilated Germany’s Army Group Centre, liberating Belarus and pushing west. Soviet troops advanced through Poland, Romania, Hungary, and into the heart of Germany. On May 2, 1945, Berlin fell to Soviet forces, and on May 9, the USSR celebrated Victory Day.

The Human Cost and Political Gain

The Soviet Union emerged victorious, but the toll was staggering: at least 20 million dead, countless wounded, and vast destruction of towns, farms, and infrastructure. Yet geopolitically, the USSR gained enormous influence. Communist governments, backed by Soviet military presence, took power across Eastern Europe. The wartime alliance with Britain and the United States soon gave way to suspicion and rivalry — the Cold War was already germinating.

Further Reading:

Richard Overy – Russia’s War (1997)

Antony Beevor – Stalingrad (1998)

Catherine Merridale – Ivan’s War (2006)

Evan Mawdsley – Thunder in the East (2005)

The Tombstone of Sentia Amarantis (Mérida, Spain)

Funerary stele of Sentia Amarantis, a freedwoman shown drawing wine from a barrel—likely her daily work. Dedicated by her husband, Sentius Victor, after 17 years of marriage. 2nd–3rd century CE, Museo Nacional de Arte Romano, Mérida. Catalogue no. MNAR 676.

In the Roman city of Emerita Augusta—modern-day Mérida, Spain—archaeologists uncovered a remarkable tombstone. At first glance, it’s a simple funerary relief. But on closer inspection, it tells a vivid, personal story: not just of death, but of life.

Carved into the stone is the figure of a woman. Her body twists slightly as she reaches for a jug with one hand, while with the other she opens the spigot of a small barrel resting on a stand. She wears a tunic pulled tight at the waist and her hair is neatly tied up. This is Sentia Amarantis, a freedwoman whose daily work—perhaps running a modest tavern—is proudly shown beside her name.

The inscription, in slightly cursive Latin, tells us:

“To the spirits of the dead. For Sentia Amarantis, aged 45. Her husband, Sentius Victor, made this for his most beloved wife. They were married for 17 years.”

The upper part of the tombstone is shaped like a small marble temple, with curved ornaments and a semicircular pediment—clearly inspired by elite monuments, but rendered in a more modest, popular style. Scholars believe this adaptation reflects both the aspirations and the economic limitations of the couple—likely former slaves.

This gravestone doesn’t show a goddess or a myth. It shows a working woman, mid-action, remembered not through abstract virtues but through the gestures of her trade. The small barrel and jug, so carefully carved, speak of labor, routine, and care.

It is a quiet but powerful monument to everyday love, work, and dignity in the Roman world.

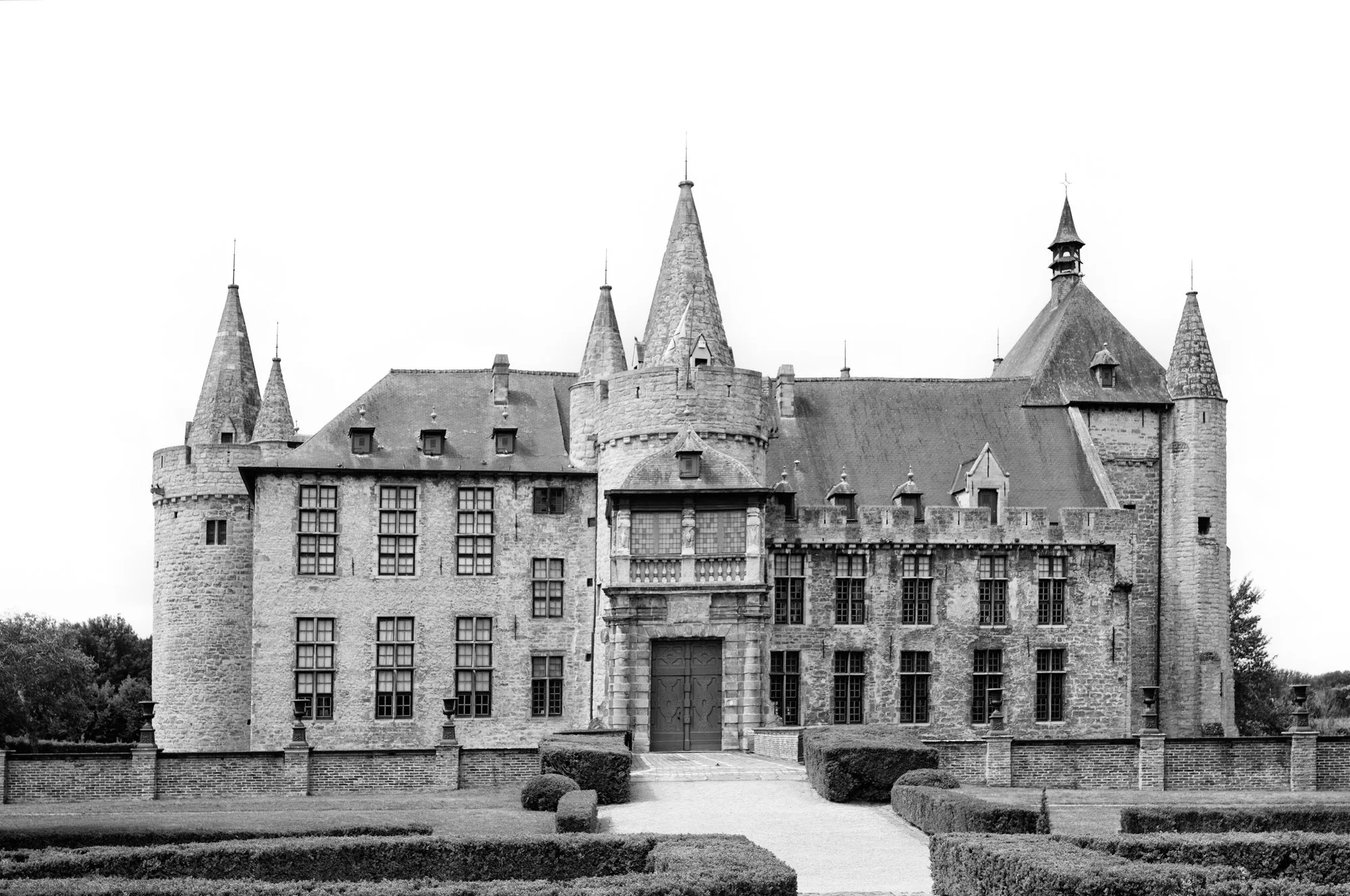

The Weeping Maid of Laarne (Belgium)

The Castle of Laarne, by Jacques Sturm (1807-1844).

Somewhere in East Flanders, just east of Ghent, sits the Kasteel van Laarne, a formidable moated fortress of grey stone and whispered memories. Its towers have seen nobles rise and fall, its walls have held courtly banquets and wartime secrets—but among its most enduring stories is one far more intimate and tragic: the tale of The Weeping Maid.

The tale originates in the 17th century, when a young maidservant named Margriet entered the castle’s service. She was a local girl, known in the nearby village for her gentle heart and striking beauty. But life behind the thick stone walls of Laarne was not always kind.

It’s said that Margriet caught the unwanted attention of the castle’s lord—a man of power and pride. When she resisted his advances, he turned vengeful. One stormy night, she vanished. The official word was that she had fled. But other servants spoke of a scream from the tower, muddy footprints on the cellar stairs, and a fireplace hastily sealed with new stone.

Years later, during renovations, human remains were reportedly found behind a wall near the tower. A small brooch—Margriet’s—was recovered alongside them. Since then, stories persist of strange happenings: unexplained sobbing in the halls, cold drafts from nowhere, a flicker of movement in the shadows. Some claim to have seen her—pale, dressed in servant’s garb, staring silently from a high window before vanishing into the air.

They call her the Weeping Maid.

The Castle of Laarne in 2025.

The Gravestone of Lutatia Lupata

Gravestone of Lutatia Lupata, a 16-year-old girl shown playing a stringed instrument. Erected by her nurse, Lutatia Severa, in a gesture of deep affection. Late 2nd century CE, Museo Nacional de Arte Romano, Mérida. Catalogue no. MNAR 6033.

Deep in the Roman city of Emerita Augusta (modern-day Mérida, Spain), archaeologists uncovered a small but touching monument: the gravestone of a girl named Lutatia Lupata, who died at just 16 years old. Her tombstone, carved around the late 2nd century CE, shows her not in mourning or death—but in music.

In a shallow niche framed by a miniature temple (edicula), Lutatia is depicted standing frontally, dressed in a tunic, her hands gently playing a stringed instrument—possibly a pandurium, a kind of Roman lute. It’s a rare and vivid portrait of youthful grace and everyday joy.

The inscription below reads:

"To the spirits of the dead. Lutatia Lupata, aged 16. This was made by her nurse, Lutatia Severa, who raised her. May the earth rest lightly upon you."

This wasn’t a monument commissioned by parents or a wealthy family—it was made by her nurse, who likely raised her from infancy. The word alumna tells us Lutatia may not have been a daughter by blood, but she was certainly a daughter by love.

Her grave marker—simple, intimate, and quietly joyful—reminds us that grief in the Roman world, like today, was deeply personal. Lutatia’s music may be long silenced, but her memory still plays on, carved in stone.

Saint-Mystère Remains Silent: The Tourists 07

The Swiss.

They arrived in an older red car, polished and humming softly, like it had been freshly tuned just for the journey. The Swiss couple stepped out without hurry—he in a well-pressed suit, she in a heavy wool cardigan and a skirt dotted with quiet flowers. They looked like they had stepped out of another time, or perhaps into one.

They brought their own chairs and sat near the edge of the village green, backs straight, hands folded. From a small leather bag came their lunch: thick slices of Zopf bread, cubes of Sbrinz, a tightly wrapped bundle of Bündnerfleisch, and a thermos of warm Ovomaltine. A bar of dark chocolate followed, divided evenly in silence.

They said little. Observed much. A nod here, a glance there. No sunglasses, no camera, no music. Only a sense of exactness, as if their being here had been calculated, pencilled in years ago.

They left just before dusk, without speaking to anyone.

Only the flattened grass where their chairs had stood remained.

In Saint-Mystère, no one tried to smooth it out.

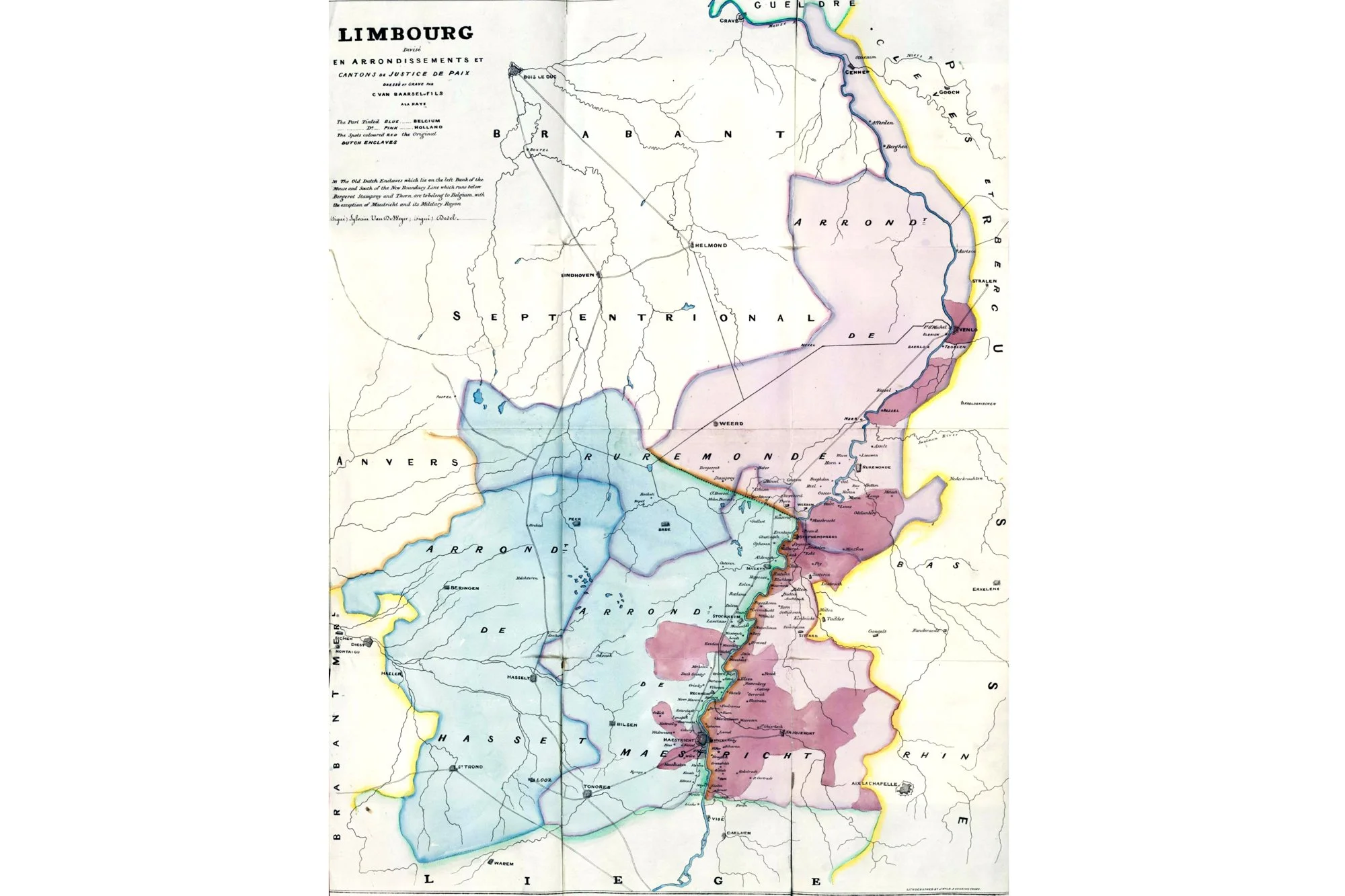

Limburg Torn Between Two Countries: Faith, Identity, and Relations with the New Order for the Low Countries after 1839

A map with the division of Limburg from the Treaty of XXIV Articles (London, 1839).

When revolution erupted in Brussels in 1830, Limburg found itself at the nexus of Europe’s great powers. For nine uneasy years, the province lived in political limbo. Belgium had declared independence; the Netherlands refused to let go. In the meantime, Limburg’s towns and villages experienced a tug-of-war not just between two capitals, but between two different worlds.

Much of Limburg’s population sided—openly or quietly—with the Belgian cause. Catholic to the core, many Limburgers felt culturally and spiritually closer to Belgium and its Church than to a Protestant-dominated Dutch state. The Catholic Church became both an anchor and a shield: an institution that spoke their language, celebrated their feast days, and upheld traditions that had shaped village life for centuries. In the uncertain 1830s, clinging to the Church was as much an act of identity as it was of faith.

Politically, the situation was volatile. In the early months of the Belgian Revolution, places like Sittard, Roermond, and Venlo joined the uprising; only Maastricht held out for the Dutch king, guarded by its fortress commander. Diplomacy played out in London’s conference rooms, with maps repeatedly redrawn—first in the so-called XVIII Articles of 1831, then in the far harsher XXIV Articles of 1839. These final terms carved Limburg in two, assigning the eastern half, including Maastricht, to the Netherlands.

The decision was met with resentment on the ground. Limburgers had grown accustomed to the broader freedoms they enjoyed under Belgian administration during the 1830–1839 interlude. Many resisted the new Dutch order: over 3,500 people formally opted for Belgian nationality, and thousands more quietly crossed the border. Even for those who stayed, the bond with “Holland” was thin. Daily life—markets, schooling, professional networks—often still pointed south to Liège, Hasselt, and Brussels rather than north to Amsterdam or The Hague.

In this climate, the Catholic Church’s role deepened. It provided continuity in a time when political allegiance was in flux. Parish life, religious festivals, and clergy influence became subtle markers of a Limburg identity distinct from the Dutch national narrative. For decades afterward, this sense of difference lingered. By the time Limburg was fully integrated into the Netherlands in the late 19th century, its Catholic heritage was not just a religious fact—it was a quiet statement of who they were, forged in the shadow of a political split.

Further reading

Piet Lenders, Honderdvijftig jaar scheidingsverdrag België–Nederland en de opsplitsing van Limburg, 1989

W. Jappe Alberts, Geschiedenis van de beide Limburgen, 1972

K. Schaapveld, Local Loyalties: South Limburg During the Belgian-Dutch Separation, 1998

L. Cornips, Territorializing History, Language, and Identity in Limburg, 2012

Europe at the Crossroads

Europe stands on a knife-edge. While China relentlessly builds and the United States races ahead in technology, the European Union risks drifting into slow decline—economically weaker, strategically dependent, and exposed to forces it cannot control. The Draghi report on EU competitiveness warns that without decisive action Europe will forfeit not only growth but its ability to defend its way of life.

The threats are multiple and reinforcing. Industrial capacity has thinned as factories moved abroad; vital know-how in energy technology, semiconductors and advanced manufacturing erodes further each year. Clean-tech ambitions clash with energy costs that remain far higher than in the U.S. or China. Fragmented capital markets and labyrinthine rules slow down every promising innovation until competitors elsewhere seize the lead. At the same time China dominates global supply chains for rare earths, batteries and pharmaceuticals, leaving Europe exposed to political leverage from Beijing.

To these economic headwinds comes the hard edge of security. Russia’s full-scale war on Ukraine is no longer a distant regional conflict but a strategic earthquake. A revanchist Kremlin openly threatens NATO’s eastern flank, tests Europe’s airspace and cyber-defences, and bets on Western fatigue. A continent that struggles to produce artillery shells fast enough, or to coordinate its own air-defence procurement, cannot assume that the U.S. nuclear umbrella will always suffice. Economic fragility and military vulnerability feed each other: a weaker industrial base makes rearmament harder, while insecurity discourages long-term investment.

What Europe needs is not another round of cautious communiqués but a surge of purposeful action. The Draghi report calls for hundreds of billions in annual investment to rebuild manufacturing and energy systems, but money alone will not be enough. Decision-making must be faster, regulation simpler, and the single market finally completed so that ideas, capital and skilled workers can move as freely as ambition demands. Industrial policy must target critical sectors—clean energy, digital infrastructure, advanced defence technologies—while integrating climate goals with competitiveness rather than setting them in tension.

Europe has shown before that it can reinvent itself when the stakes are existential. Today the choice is stark: either remain a mosaic of well-meaning but slow-moving states, or act as a true union capable of building, defending and innovating at scale. The alternative is a future where prosperity ebbs, dependence grows and security is left to others. In an age when power belongs to those who can out-build and out-last their rivals, Europe must decide whether it wants to shape the century—or be shaped by it.

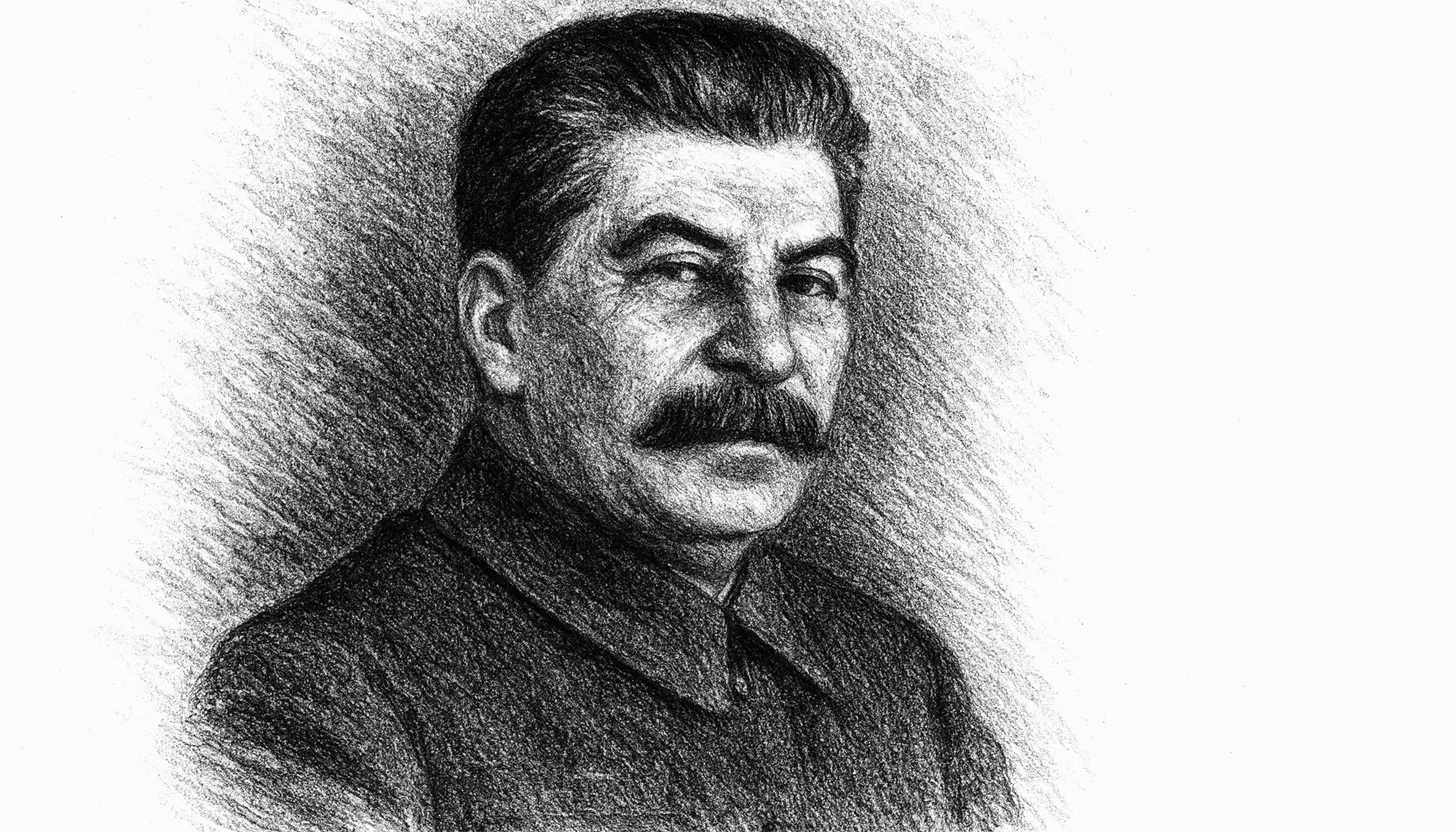

Russia, The Eternal Return of Suppression: From Lenin to Stalin - Building the Soviet State

Joseph Stalin

The birth of the Soviet Union in 1922 was both the conclusion of the revolutionary struggle and the beginning of a new experiment in governance. The Bolsheviks had won the Civil War, but they inherited a country ravaged by years of conflict, famine, and economic collapse.

Lenin’s Pragmatic Retreat

To stabilize the economy, Lenin introduced the New Economic Policy (NEP) in 1921. It was a tactical retreat from full socialism: small businesses and private markets were allowed to operate, peasants could sell surplus grain, and foreign investment was cautiously welcomed. The policy brought modest recovery, but also ideological unease among hardline communists.

The Succession Struggle

When Lenin died in January 1924, he left no clear successor. The ensuing power struggle pitted Leon Trotsky — charismatic leader of the Red Army — against Joseph Stalin, the party’s General Secretary. Stalin used his position to quietly build alliances, control appointments, and marginalize rivals. By the late 1920s, Trotsky was exiled, and Stalin stood unchallenged.

The First Five-Year Plan

In 1928, Stalin launched the First Five-Year Plan, aiming to transform the USSR from an agrarian economy into an industrial superpower. Massive projects such as the Dnieper Hydroelectric Station and the Magnitogorsk steelworks became symbols of progress. Industrial output surged, but at tremendous human cost — workers endured harsh conditions, shortages, and strict discipline.

Collectivization and Famine

In the countryside, Stalin forced millions of peasants into collective farms. Those who resisted — labelled “kulaks” — were deported or executed. Grain was requisitioned to feed cities and finance industrialization, even during poor harvests. The result was famine on a massive scale. In Ukraine, the Holodomor of 1932–1933 killed millions, a trauma that still shapes Ukrainian–Russian relations.

The Great Terror

By the mid-1930s, Stalin’s paranoia turned inward. A wave of purges swept the Communist Party, the military, and the intelligentsia. Show trials extracted confessions through torture; executions and Gulag sentences followed. Entire generations of revolutionary leaders vanished. Yet even as fear spread, the Soviet state consolidated its grip, and Stalin’s image as the “Father of Nations” was cultivated through propaganda.

The Soviet Union on the Eve of War

By the end of the 1930s, the USSR was a formidable industrial power with a centralized command economy. The human toll had been immense, but Stalin believed the sacrifices had prepared the country for the challenges ahead — challenges that would arrive sooner than anyone expected.

Further Reading:

Stephen Kotkin – Stalin: Paradoxes of Power (2014)

Robert Service – Stalin: A Biography (2004)

Orlando Figes – Revolutionary Russia 1891–1991 (2014)

Sheila Fitzpatrick – Everyday Stalinism (1999)

Lampa, the Mystery Girl of Roman Mérida (Spain)

Marble relief of a naked female figure with the inscription “LAMPA” above her head. Found in Augusta Emerita (modern Mérida), 2nd–3rd century CE. Museo Nacional de Arte Romano, Mérida.

In a quiet gallery of the Museo Nacional de Arte Romano in Mérida, a small marble plaque draws the eye. A young naked female is carved into its surface, her posture elegant and reserved—one hand resting over her chest, the other hanging by her side. Modest in size and style, the relief seems classical, serene. But look closer, and the story deepens.

Above her head, in Greek letters, is a single word: LAMPA. Next to it, also in Greek, her age: thirteen.

From the start, scholars noted that the use of Greek—and the very young age—might suggest that this figure was not a goddess or an elite Roman matron, but a foreign girl. Some early interpretations proposed she was commemorated in death. But newer readings have shifted the focus.

The plaque was found in the necropolis of Augusta Emerita, reused in a later burial. Yet its original purpose may have been something else entirely. Her hairstyle matches that of Faustina the Elder, dating the image to the mid-2nd century CE. Her pose—nude, decorative, and non-mythological—aligns with known depictions of women linked to the world of Roman brothels, or lupanars.

The theory now gaining ground is that this relief once adorned the façade of a brothel, and that Lampa, whether her real name or not, represents one of the many young, likely enslaved, girls who worked within. The Greek language reinforces this possibility, as Greek was often used for names of non-citizens and enslaved people in Roman Hispania.

Whether Lampa was a specific girl or a symbolic name advertising youth and availability, the effect is haunting. She may have been only thirteen—an age etched into stone, but robbed of voice, context, and choice.

Today, she stands silent in marble. Not a goddess. Not a noblewoman. But a girl, remembered not through love or honor, but through commerce and objectification. A body preserved. A childhood lost.